MDF: Magical Defense Force is a visual novel following a mean-spirited young man who finds himself drawn against his will into a conflict between a team of magic girls and an enigmatic organization creating legions of humanoid monsters. It primarily deals in comedy and action, occasionally flirting with light drama. While I don't believe it has an age rating, it seems to be written for an adult audience rather than young children, containing occasional use of profanity, onscreen violence, and a few references to sexuality. It specifically falls into the kinetic novel subgenre, offering no branching paths or interactions, but instead focusing entirely on storytelling enhanced by visuals and audio. It's available in English on Steam and delivered in episodic format. There's also a demo, although I'm not sure what exactly it covers.

As a necessary preface, I didn't stumble on this game at random. I'm a member of a Discord server with one of the developers, and perhaps due to shared interests, he gifted me the first set of chapters of this game. I wasn't asked for feedback and I don't think he was even that aware that I also frequent ResetEra, but if I'm given a gift, I figure that it's polite to give something in return, and the least I can do is provide a review. This isn't meant to be just an ad for the game, so I'm going to try to really sink my teeth in while remaining even-handed in describing its strengths and weaknesses, but it's probably worth bearing in mind how it might affect what I'm comfortable with saying.

I wanted to start us off with a little history lesson regarding the magical girl genre and some discussion of my own experience with it so that we can all approach MDF with a similar baseline of understanding, but it's going to add a significant chunk of reading to what I expect to be an already article-length OP, so I'm going to put in spoiler tags. Feel free to read it if you're interested in the genre in general, or else we can proceed straight to the game review.

The magical girl genre begins in the 1960s, at a time when manga was still very much a male-dominated industry, even when aiming for a female audience. Specifically, its origins are often credited to the American sitcom Bewitched, which I imagine you may already be familiar with since it was popular in reruns for a long time; it revolves around a witch with seemingly limitless powers who tries to live as a normal mortal American housewife, but frequently ends up both causing problems and getting out of them through the use of her magic. The first magical girl manga, Himitsu no Akkochan, actually predates Bewitched by a few years despite the author giving it credit – it's possible that he was confusing it with an earlier American movie, I Married a Witch – but the first animated take on the genre, Sally the Witch, debuted not long after the Japanese dub of the show. With Sally's success, Akkochan also received an animated adaptation inheriting its time slot, and magical girl anime secured a constant presence.

It's worth noting that much like Bewitched, magical girls of this era were more in line with comedies featuring powerful main characters dealing largely with everyday life. While it's possible that the protagonist might get into fights, comedy rather than action was the major focus of the story, and there wasn't a strong consistent villainous presence to oppose the hero. This classical style of magical girl series never went away, but it's rarely attained a big international presence, including in English-speaking territories.

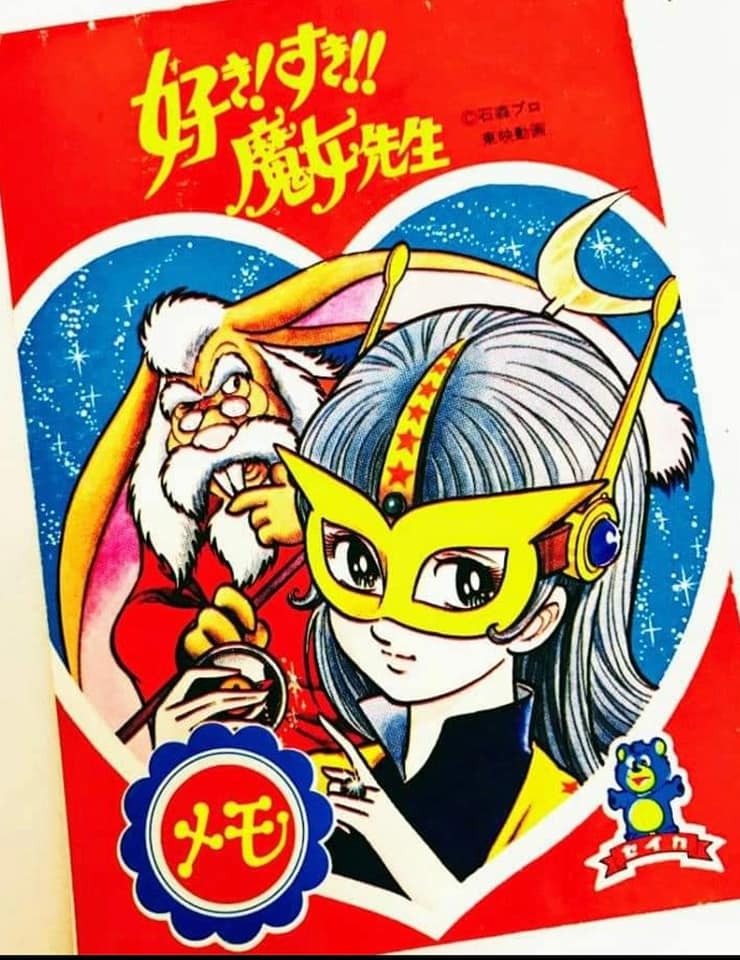

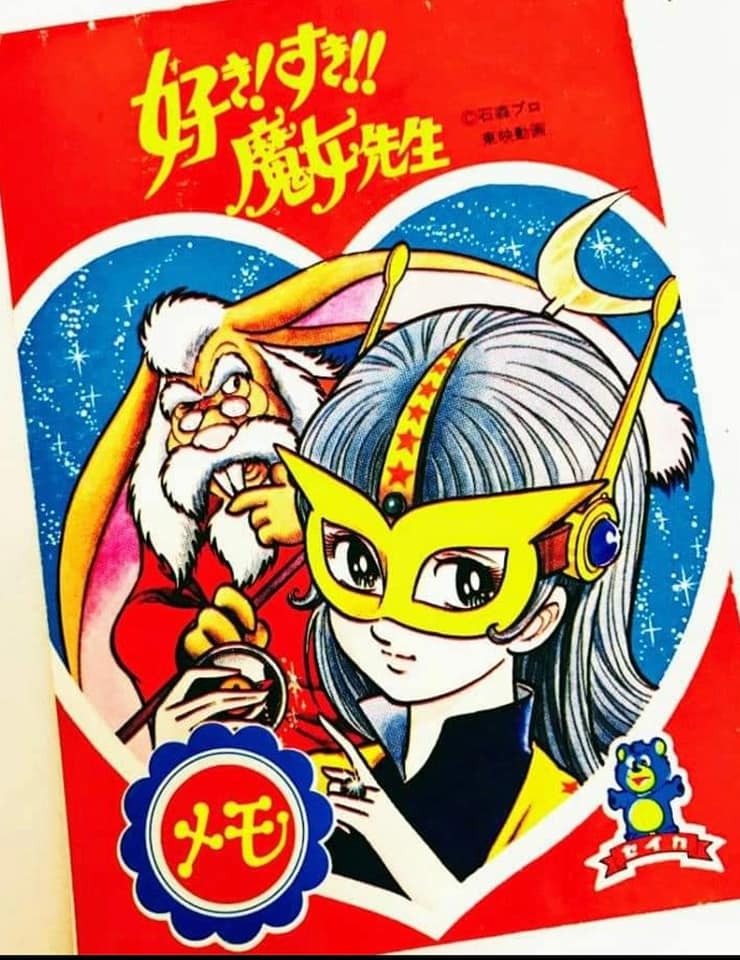

In the 1970s, transforming human-scale superheroes were popularized in Japan by series such as Kamen Rider and Super Sentai, often having the hero fighting back against some kind of evil organization. As a result, there was an increasing number of series which combined magical girls with this format. The earliest one I'm aware of is Love! Love! Witch Teacher, originally a comedic magical girl live action series by the creator of Kamen Rider which then changed gears partway through and had its protagonist transform into a superheroine by the name of Andro Mask. Cutey Honey is often viewed as a magical girl superhero series, although it was aimed at boys and contained a lot of the titillation that its creator was making his career on. At the same time, women were making huge strides in manga aimed at girls, often pushing them into more dramatic territory with heavier themes. However, the magical girl genre was not driven by female creators at this time to my knowledge.

The 1980s the genre apparently experienced another wave of popularity, perhaps influenced by idol entertainers being at the height of their own popularity and expanding the interest in female-led series to male audiences. The end of the decade included remakes of both Himitsu no Akkochan and Sally the Witch, and it also led to a new series of live action transforming superhero magical girl shows spearheaded by Kamen Rider's creator starting with Magical Chinese Girl Pai Pai!. But I'm more interested in heading over to the 1990s. At the start of the decade, Magical Chinese Girl Pai Pai! received an even more popular successor, La Belle Fille Masquée Poitrine. It's shortly after Poitrine finished airing that Naoko Takeuchi used it for the basis of her manga Codename: Sailor V, which was then mixed with elements of Super Sentai to become Sailor Moon.

The influence of Sailor Moon cannot be overstated. Beyond simply being an extremely popular magical girl series even beyond its primary target audience, it was part of the early wave of English-translated anime that pushed anime into mainstream children's entertainment in English-speaking territories. As a result, it's often internationally the face of the magical girl genre as a whole, if not one of the faces of anime itself for quite some time; when the magical girl genre is in discussion, it's often Sailor Moon specifically that people imagine. The transformation sequence is itself iconic, frequently subject to imitation and tribute.

While it's by far the biggest, Sailor Moon wasn't the only popular magical girl series to come out of the nineties; I think in general, it's the period where women starting taking more control over the genre. In later decades, dark or subverted magical girl media seems to have also become a popular trend, such as Puella Magi Madoka Magica. But the evolution that led us to Sailor Moon is what I'm most interested in for this discussion, since I believe that Sailor Moon is also the biggest influence for the game we'll be looking at.

For me personally, I'd usually say that I'm a mecha nerd rather than a general purpose anime nerd, so while I'm aware of a lot of this on paper, my actual viewing history for magical girl media is pretty shallow. Aside from watching a certain amount of Sailor Moon, I did enjoy Cardcaptor Sakura, which I believe is a little more in line with the older style, as well as an example of how magical girl media in the nineties was being more driven by female creators. I've also had a certain amount of exposure to Magic Knight Rayearth by the same creators.

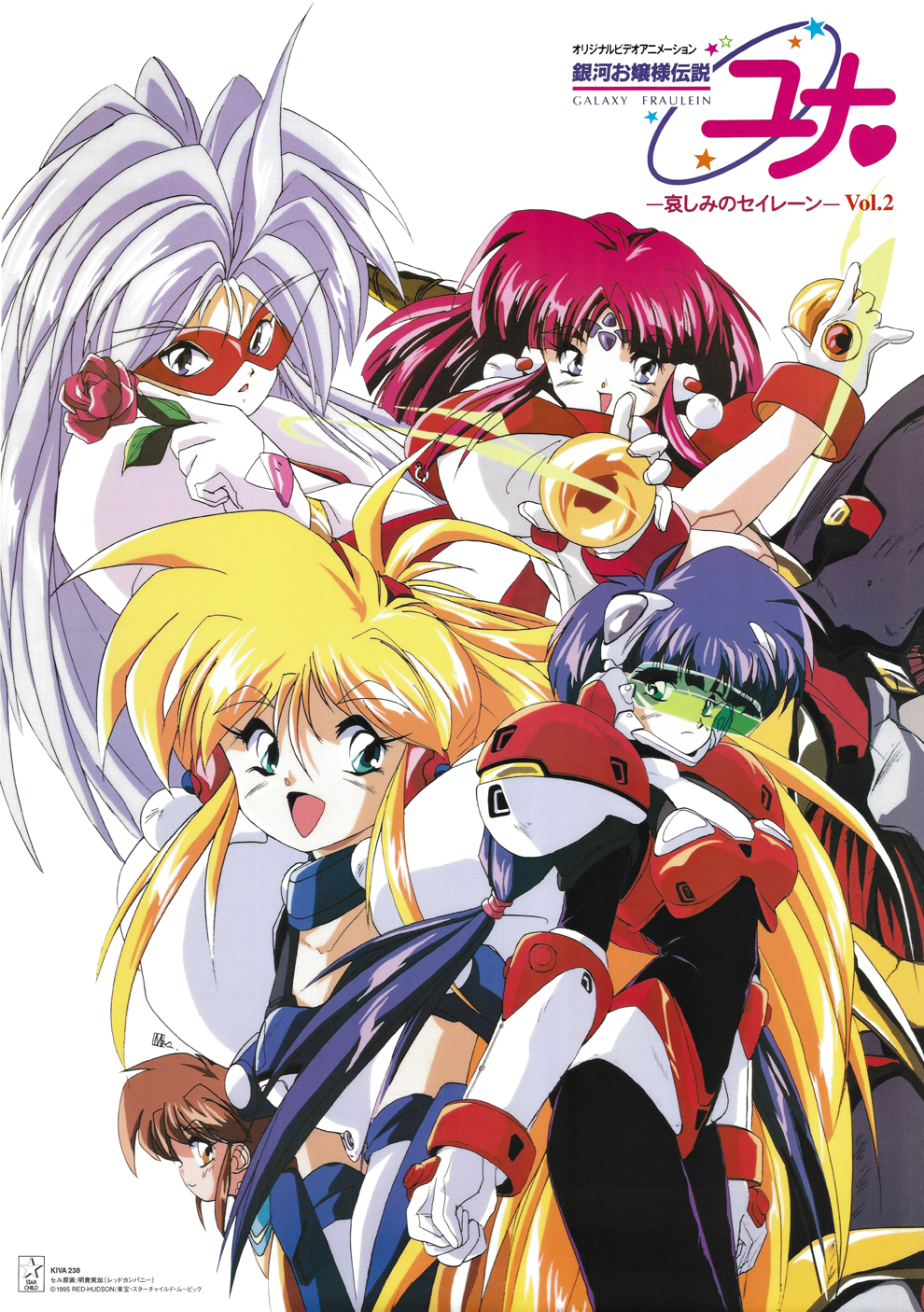

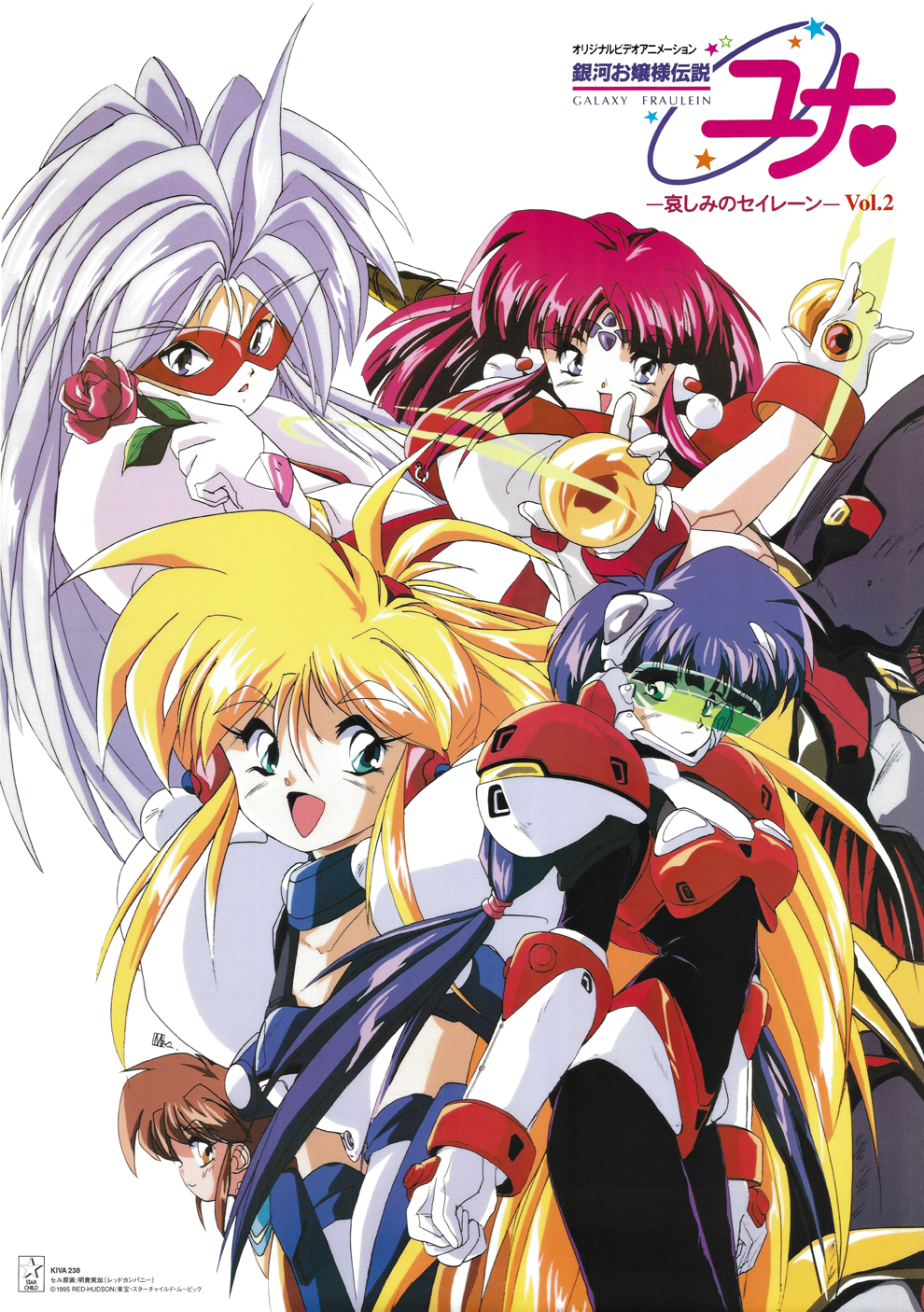

Aside from that, I've bumped into a bunch of magical girl stuff where it aligns more with the stuff that I normally watch, but those are generally more aimed at a male audience and often feel more exploitative. I was recommended the original Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha back in the day, which was intended as an action-focused series that styles itself after Gundam. Maybe later series in the franchise are better, but the first one had a lot of panty shots and changing scenes and things like that, which coupled with Nanoha's flat and unblemished personality read as very fetishistic to me. The earlier Galaxy Fräulein Yuna was a similar concept, being inspired by the MS Girl design motif that reimagines the Mobile Suits from Gundam as costumes. It seemed to be to be more inoffensive, but also very shallow, feeling like a showcase for cute designs without much interest in developing characters to go with them. Dangaizer 3 was a late entry in the wave of retro mecha OVAs in the eighties and nineties, differentiating itself by also being an early dark magical girl story with skimpy costumes and a heavy focus on sex appeal.

Because of stuff like this, I tend to be more apprehensive to magical girl works by male creators and which seem to be focused on a male audience; my major concern is that the characters are meant more to be looked at by the audience than to be seen as humans which can be related to.

As we proceed into the review of this game, hopefully this gives an idea of how I'm trying to contextualize the game and what the pitfalls are that I'm watching out for.

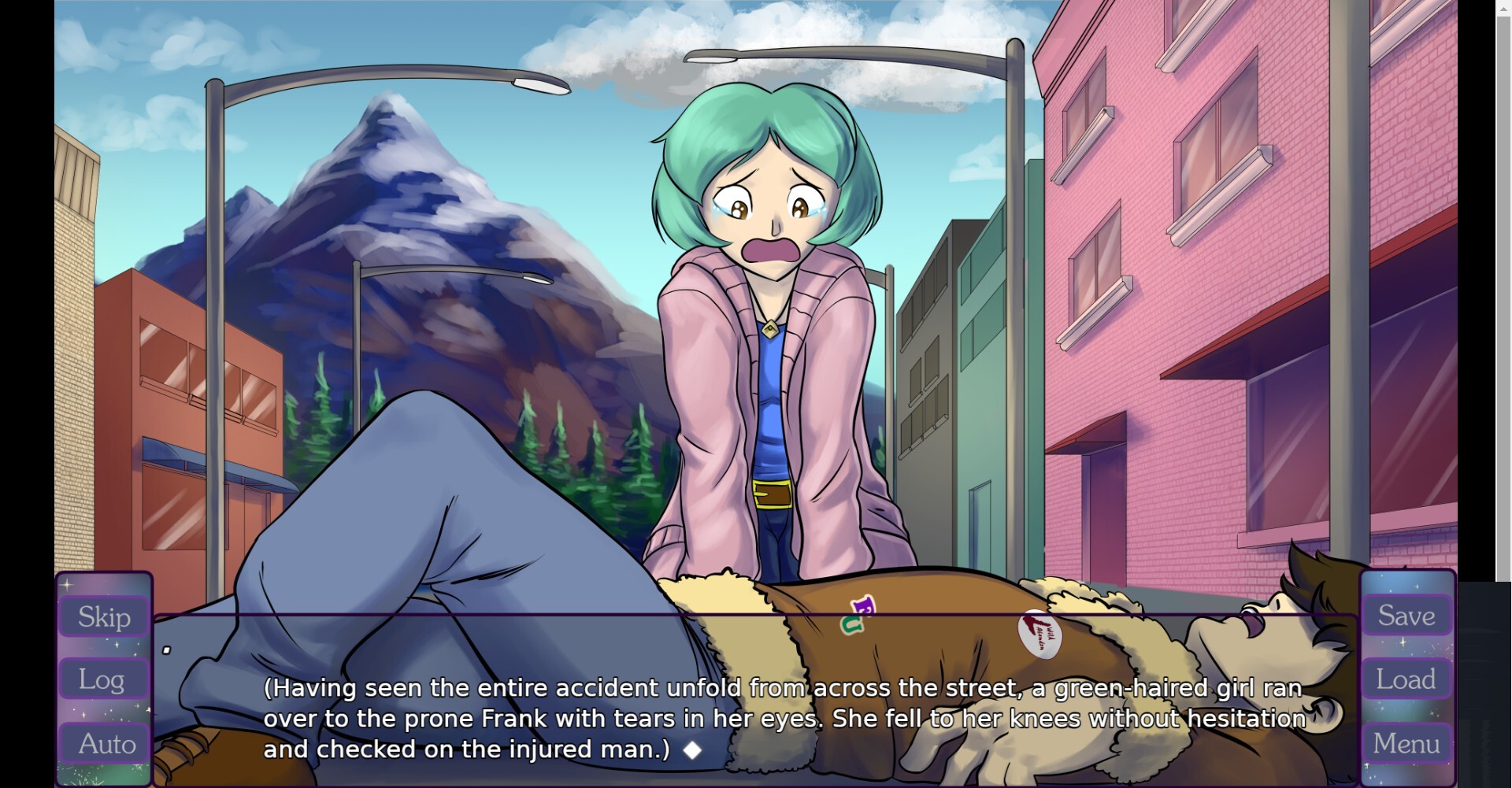

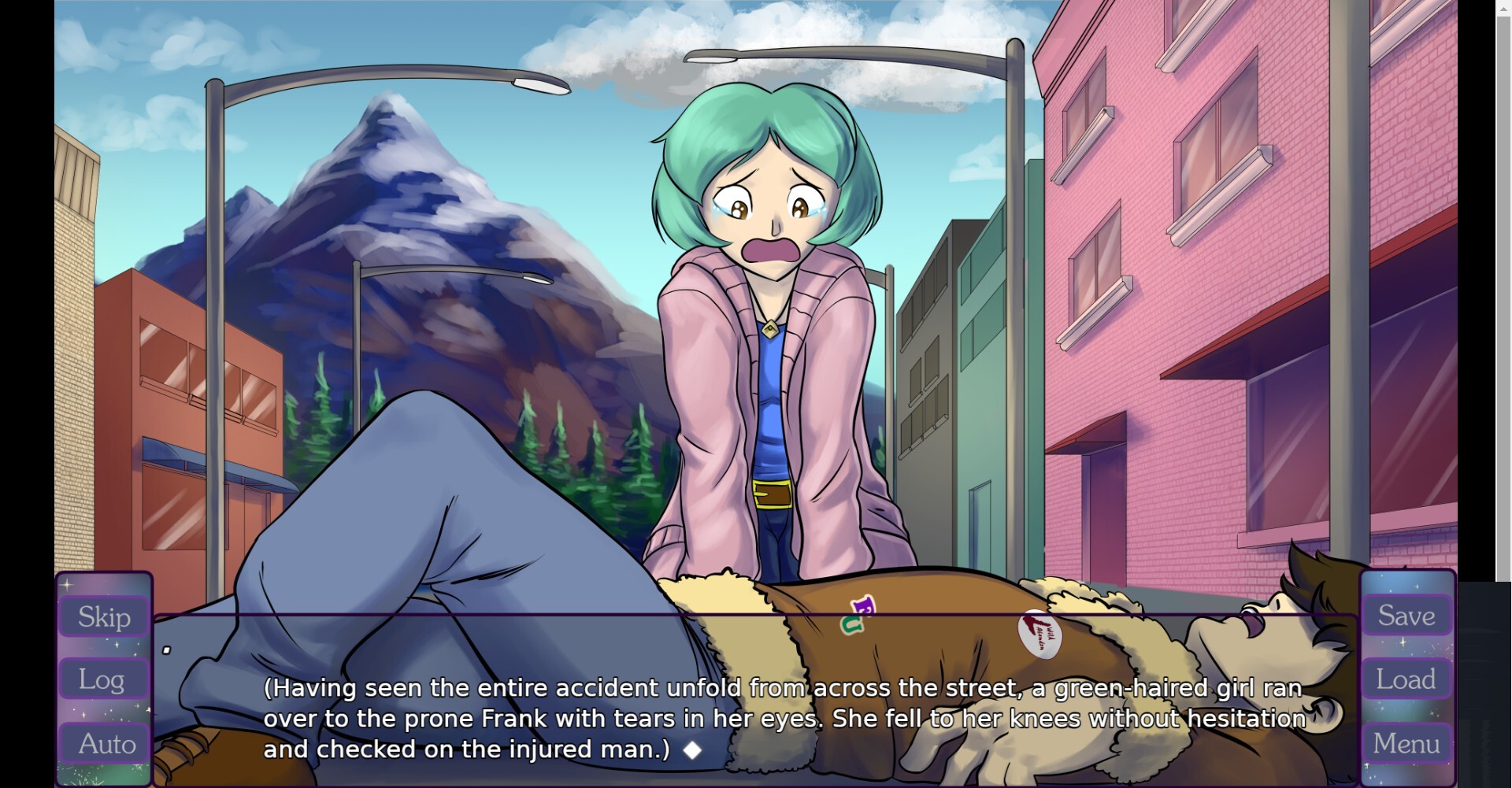

The basic premise of MDF: Magical Defense Force begins with Frank, the antisocial and truant student who serves as our main character, finding himself using improvised weapons to assist a bubbly magical girl named Michiki in a battle with a monster. Despite his protests, Michiki then forcibly intrudes into Frank's life, insisting that they work well together. While the story primarily follows Frank, Michiki, and their friends as they fight against different monsters every episode and try to assemble their full magical girl team, we also have frequent glimpses of the mysterious evil organization conspiring against them led by Mary-Anne, who often seems less outright evil but more cranky and disrespectful to her subordinates.

I imagine that anyone who grew up with Sailor Moon would already start seeing how this might feel like it's modeling itself off of that series. Michiki fits with Sailor Moon herself, the leader of the team who is a bit of a doofus but still a capable hero. The team resembles the Sailor Senshi, including that part of the quest is to assemble them rather than the team being assembled all at once. Mary-Anne maps up to Queen Beryl, who we frequently see scheming against the Sailor Senshi early in the series, perhaps the series' villains in general.

But in part these connections often map up to the standard roles in Super Sentai or similar works that Sailor Moon was also working off of, and there are also things missing or elements that don't really line up well to anything in Sailor Moon. As the player continues through the game, the semblance feels thinner. In fact, part of the reason why I connect MDF so much to Sailor Moon is that a lot of the tropes that it adopts or plays with aren't specific to the magical girl genre, but are present in Super Sentai and other Japanese superhero works; it might even evoke those harder than it does with magical girls. It ultimately comes across less that the game is trying to be understood as a response to Sailor Moon and more that it uses it as a structural reference point which it can then deviate from as desired.

Frank doesn't do anything more extreme than flipping the bird constantly and using gendered insults, but he's still very much a negative character; he spends much of the time complaining or picking fights with others, including people who are friendly to him. It's easy to imagine that this sort of character could end up being sincerely unlikable to the detriment of the story as a whole, but it's balanced out in two ways. The more commonly seen factor is that, with him being the protagonist of a comedy, Frank is constantly punished rather than allowing us to dwell on his negativity. While he's a contributing member of the team, he gets dunked on too often to make us feel that the game wants us to see him as the coolest one.

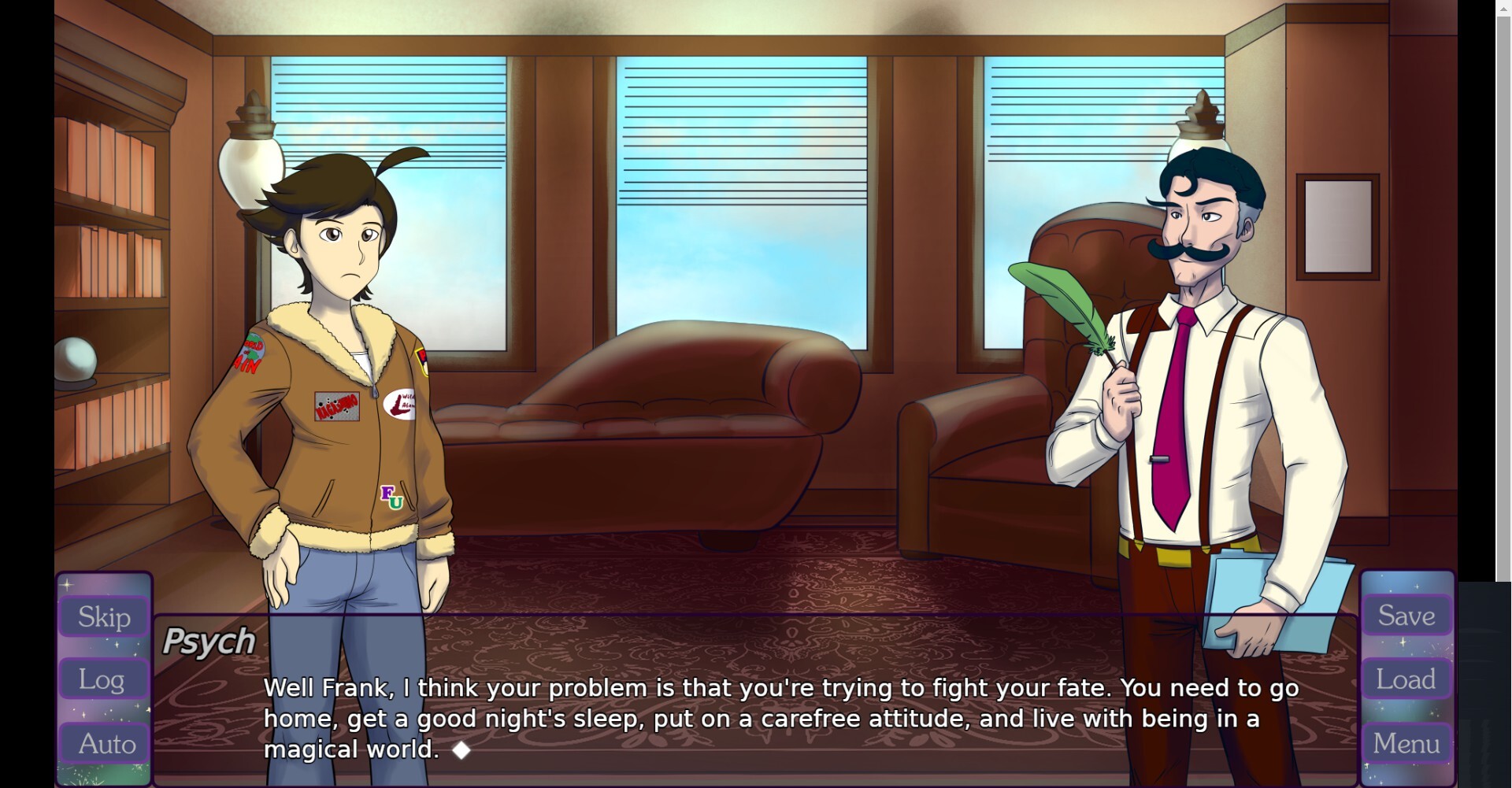

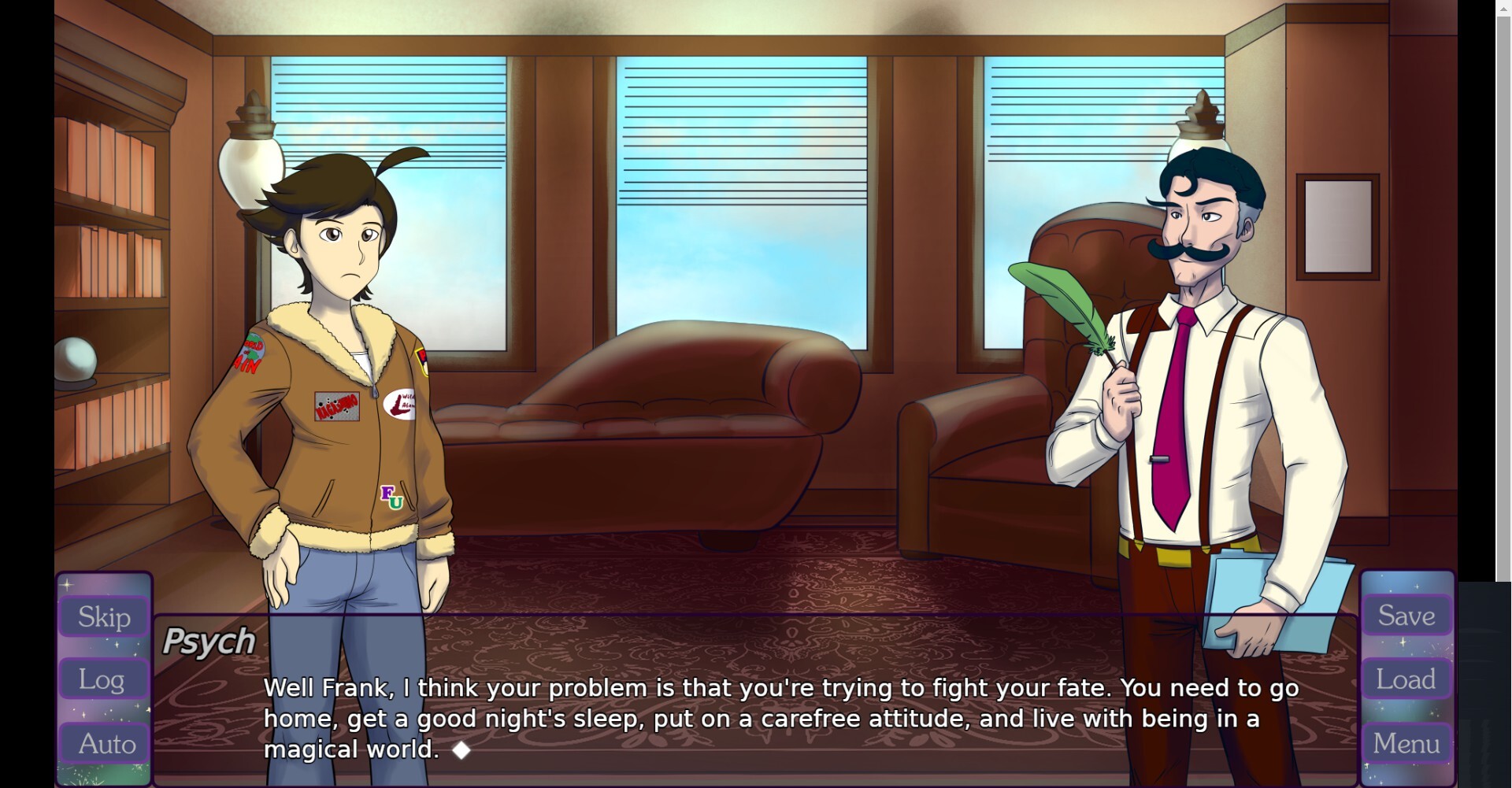

The other thing is that the game establishes quickly that the trajectory this story will follow is most likely going to be a journey of personal growth and redemption for Frank. The first episode has a framing device where he's telling the story to a therapist, which already puts things through the lens of reflecting on what his life is like and how it can be improved. While the spotlight is primarily given to the magical girls' battle against evil, Frank's development is still occasionally brought up, suggesting that it's going to be an overarching point that will culminate as the story progresses. That this all comes up because of the more optimistic Michiki evokes a particular trope which I imagine there's a lot written on, but I personally feel like I relate strongly to the idea of having your life benefit from having strong relationships with women such as friends and family, and I think it's written in a way that the magical girls' adventure feels like something that exists independently and is important without Frank even if he benefits from being included in it.

The characters may at least at first feel a little shallow, which I suspect is in part due to MDF's story demands and writing needs. Because of the comedy focus of the game, characters are often established as comedic devices first and foremost, being more of a gimmick that can be described in a word than seeming like they're complex people who are built out of their personal histories. That said, little dramatic moments throughout the game do slowly build some of the characters up over time. There are also extra scenarios included in the game - short optional stories that don't really matter to or fit into the main plot - which serve largely to show off interactions between characters that aren't explored as much or just to provide more opportunity to flesh the characters out. These are very short scenes, so none of these scenes are too exciting; I'd say my favourite of them has the punk girl Hoshune chew out wacky conspiracy theorist Lee for his failure to recognize real government abuse.

The leader of the magical girls, Michiki, strikes me as a particularly strong example of how the nature of the story affects how the characters are written. Looking at Sailor Moon functionally, Usagi is a layered character because she's the audience's viewpoint character; she's the one who is closest to us in the audience in how she understands the story, and who we are most expected to project ourselves into to engross ourselves in the story. Transforming magical girls have often represented transition to adulthood, such as Marvelous Melmo or Minky Momo using magical means to physiologically transform from girls to women. Usagi instead represents that thematically through the distinct layers in her personality, her normally possessing the negative traits that we tend to see in ourselves such as clumsiness, laziness, and stupidity, but through becoming Sailor Moon being able to reach her potential and express her capacity for strength, confidence, and grace. In MDF: Magical Defence Force, it's instead Frank that's the viewpoint character and who expresses the negative traits, not Michiki. Michiki as a function instead better resembles Sailor Moon's Luna, the character who serves as our link with the fantasy world, providing our information about how it works and what our mission is. She already starts off expressing a level of competence, so while she also tends to be clumsy, her flaws aren't as sharply delineated from her strengths.

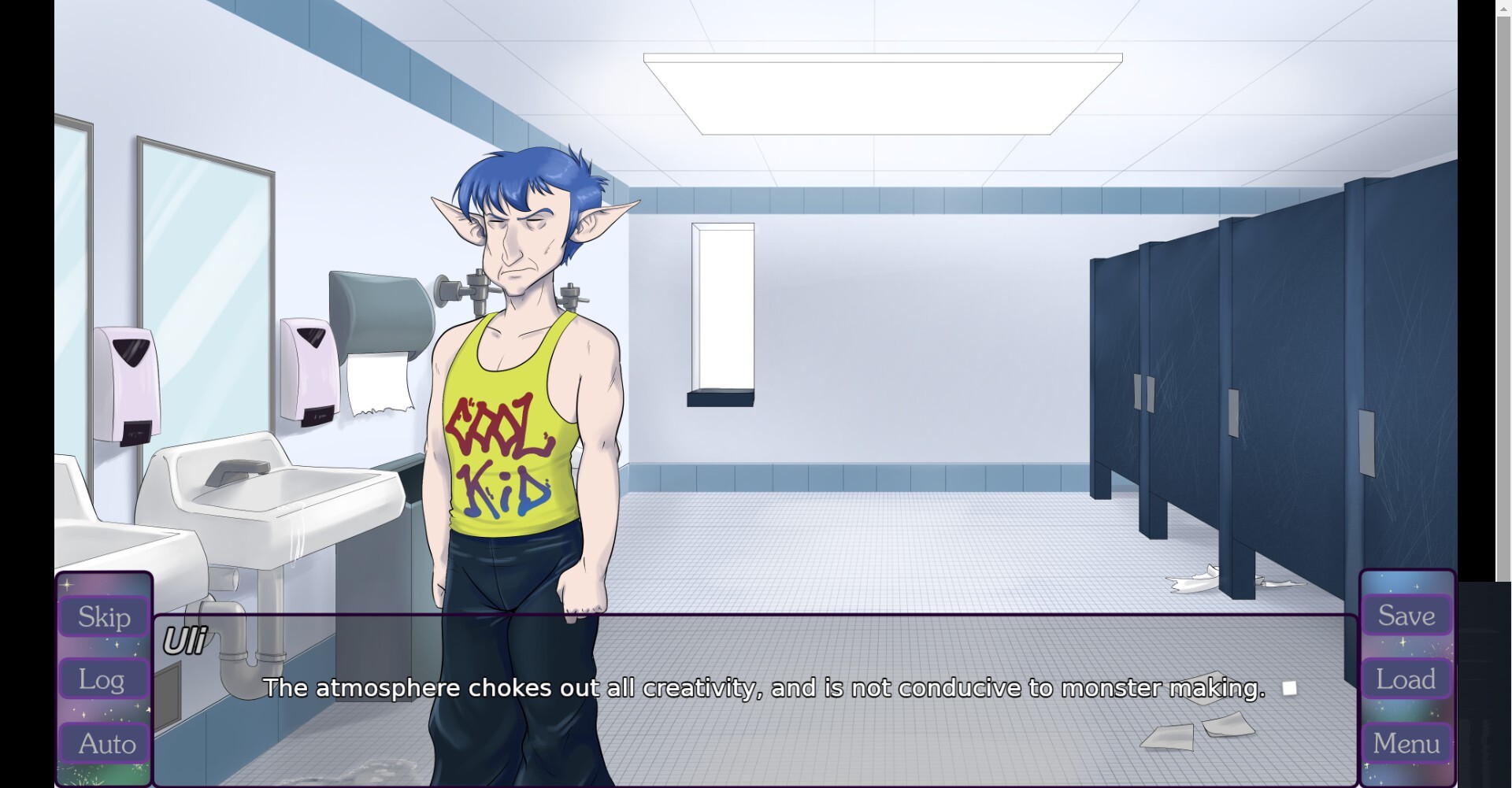

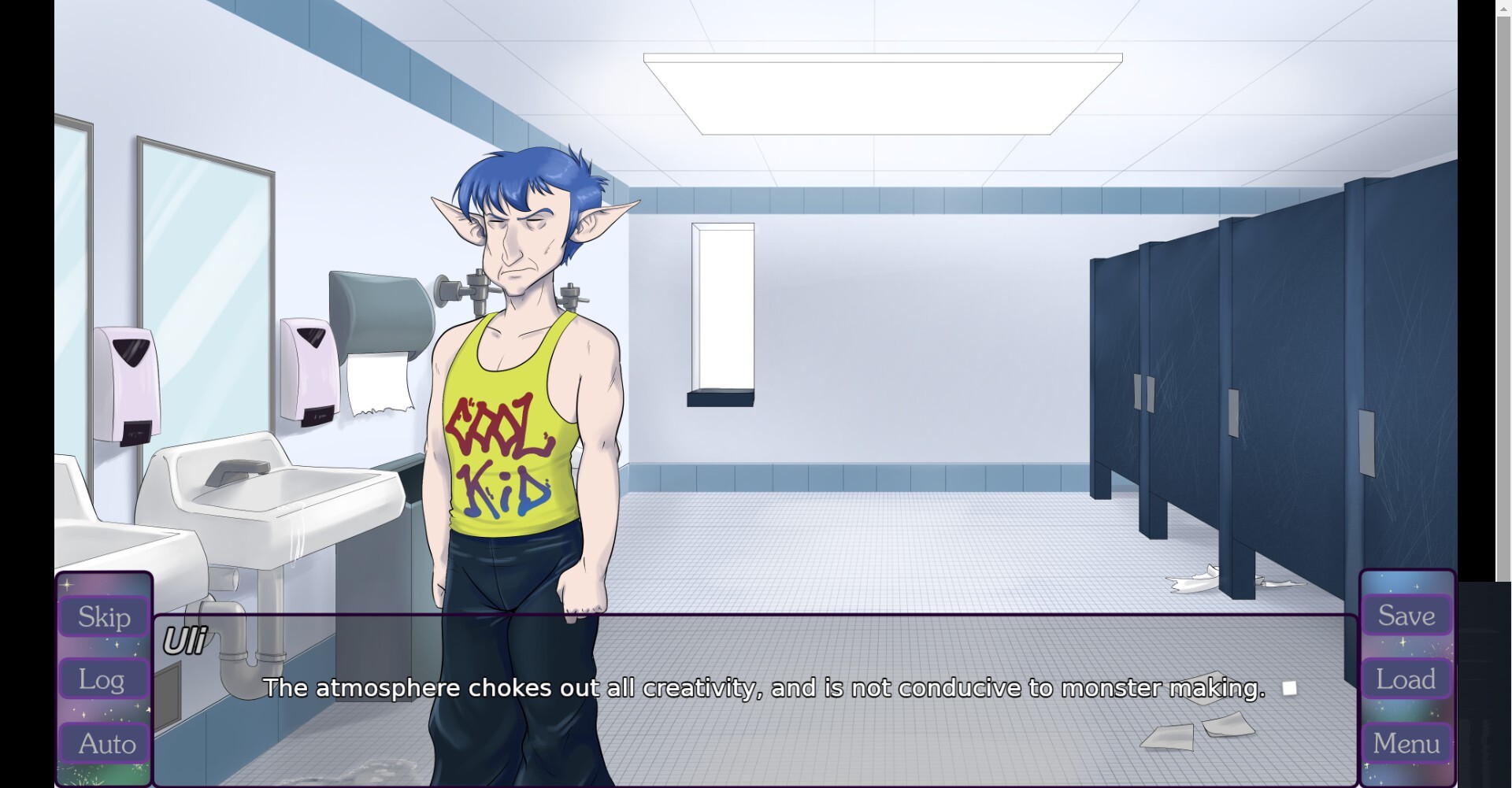

Trying to think of my favourite character, I feel like the game's attempt to gradually build its characters up becomes visible. An early favourite of mine is Uli, the long-suffering monster maker. He feels very much like a Super Sentai character concept, similar to Pleprechaun from Zyuranger, but the game gets a lot of humour of pushing him more into the foreground rather than having him as just a background fixture to justify the existence of the monsters. But as the story continues, I gravitated more towards Hizatchi, Frank's best friend. He seems very stoic and even brutish, but the longer we spend to him the easier it is to notice that he's mostly seen helping others, and he's the character who seems more aware of others' emotions while also feeling no hesitation in caring for them.

The setting of MDF doesn't quite seem to be our real world, even if it's similar. The country the story takes place in is a fusion of America and Japan similarly to how Los Angeles is depicted in the localized version of Phoenix Wright. While it's probably meant to be silly, it isn't a one-off gag, and when we hear the names of other countries, they also seem to be similar amalgams. It comes across less as purely riffing on questionable localization decisions and more a conscious adoption of the accidental awkwardness produced by that setting; because the setting is both America and Japan, it can use tropes seen in anime that come from the Japanese experience without having to call attention to them as abnormal, while it can also feature more American imagery and humour without breaking the cohesion. The characters appear to be college-aged, allowed to drive and allowed to drink, perhaps living with their parents but without visible supervision. The town they live in feels like a sleepy American suburban. However, their school experience appears to be more in line with Japanese high school, revolving around the homeroom rather than separate rooms by subject. Some characters wear Japanese school uniforms, but there's nothing to indicate that there are any rules encouraging them or that they're even worn specifically for school, so without any other acknowledgement it just comes across as a matter of personal fashion choice than anything else.

As a more subtle thing, while magic and monsters are clearly out of the ordinary, the characters in the game never seem to be phased by non-humans talking to them. The most obvious example of this is that Hizatchi, Frank's best friend, is clearly a hobgoblin. There are enough dropped opportunities to acknowledge this that makes me feel like it's a running gag, but hobgoblins don't really strike me as having anything to do with the magical girl genre or Super Sentai or other Japanese media that isn't specifically drawing off European fantasy, so I interpret it more as just a quirk of the game's setting. Presumably this is a world where non-humans with human-like intelligence are just things you see once in a way and aren't viewed as particularly notable in and of themselves by average people.

The art style reads to me as animesque rather than anime-styled, and not necessarily in a way that's intentional. That is to say, it feels to me that this is the sort of art style that results when someone learns from "how to draw anime" books or other resources which similarly attempt to reproduce the art styles seen in anime without the teacher having experience with its actual production. Perhaps the artist of the game might also still be fairly new and their skills are still in the development stage. I don't have anywhere even remotely close to the art knowledge or skill necessary to go into detail critiquing this aspect, but if you think about anime style as something related to animation, you can imagine how consistency would be mission critical to ensure visual continuity from frame to frame. Even between different characters, shape or proportion may trend towards similarity to make it easier for the artist to repeat them. That consistency isn't really visible here. At first glance, I wasn't too impressed with the art of the game; the style used isn't something I'd usually seek out.

This may sound like I'm tepid on the art in MDF, and that's largely true taking any given shot of it in a vacuum. However, I think the actual result you see on the whole is strengthened by the way that art style is utilized, to the point that I can't say it would be better for it to have a style more akin to what you typically see in television anime due to how much you'd lose. A few characters have details in their clothing that seem like they'd be a pain to animate; in particular, I'm struck by Frank's jacket being accessorized with a bunch of different slogans like the cheesy "World of PAIN" and "FU". Considering the decidedly non-uniform usage of Japanese school uniforms, it strikes me as providing an American cultural counterpoint, where more individual or cliquish personal fashion is on display even in school settings. Actually, when working on this thread, I learned that Sailor Moon's Naoko Takeuchi had originally intended the Sailor Senshi to have more individualized designs to reflect the individual personalities and tastes of the characters, which she felt was natural for girls, but those design elements were standardized development due to animation needs. It's interesting that MDF: Magical Defense Force's more individual costume design, while aiming for a simple sailor suit-inspired design much like Sailor Moon's, also has more individualized traits that might better reflect Takeuchi's original intent.

There's also a clear effort to include some diversity, both in ethnicity and body type, that we don't often see in anime trying to capture to the experience of an average girl in relatively ethnically homogeneous Japan. The most prominent example is Michiki, who is visibly chubbier than most of the other characters, which I feel is particularly surprising for the leading lady. The height of characters varies quite a bit as well, with the women not being shorter than the men with any great consistency. I also took notice of one design used to represent a few minor characters being a Sikh man, complete with kirpan and kangha; someone who doesn't look too far off from someone I might meet on an average day, but doesn't show up a lot in magical girl anime. I won't go as far as to claim that it's implemented well or poorly since that's more for the people depicted to say, I do think it would be nice to see ethnic variety from the major characters, but I think it at least demonstrates an interest in exploring more varied physical features in their designs than the source material tends to.

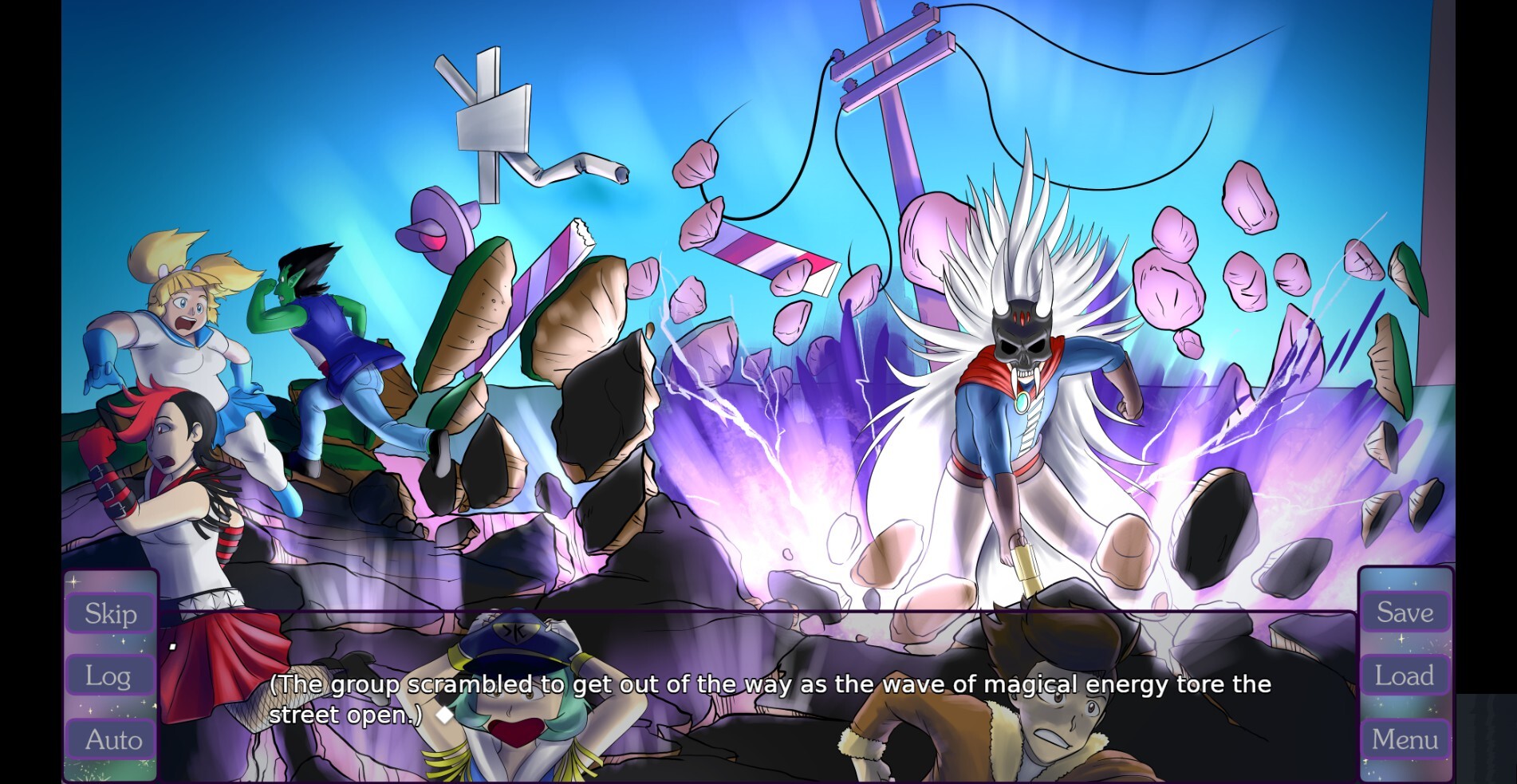

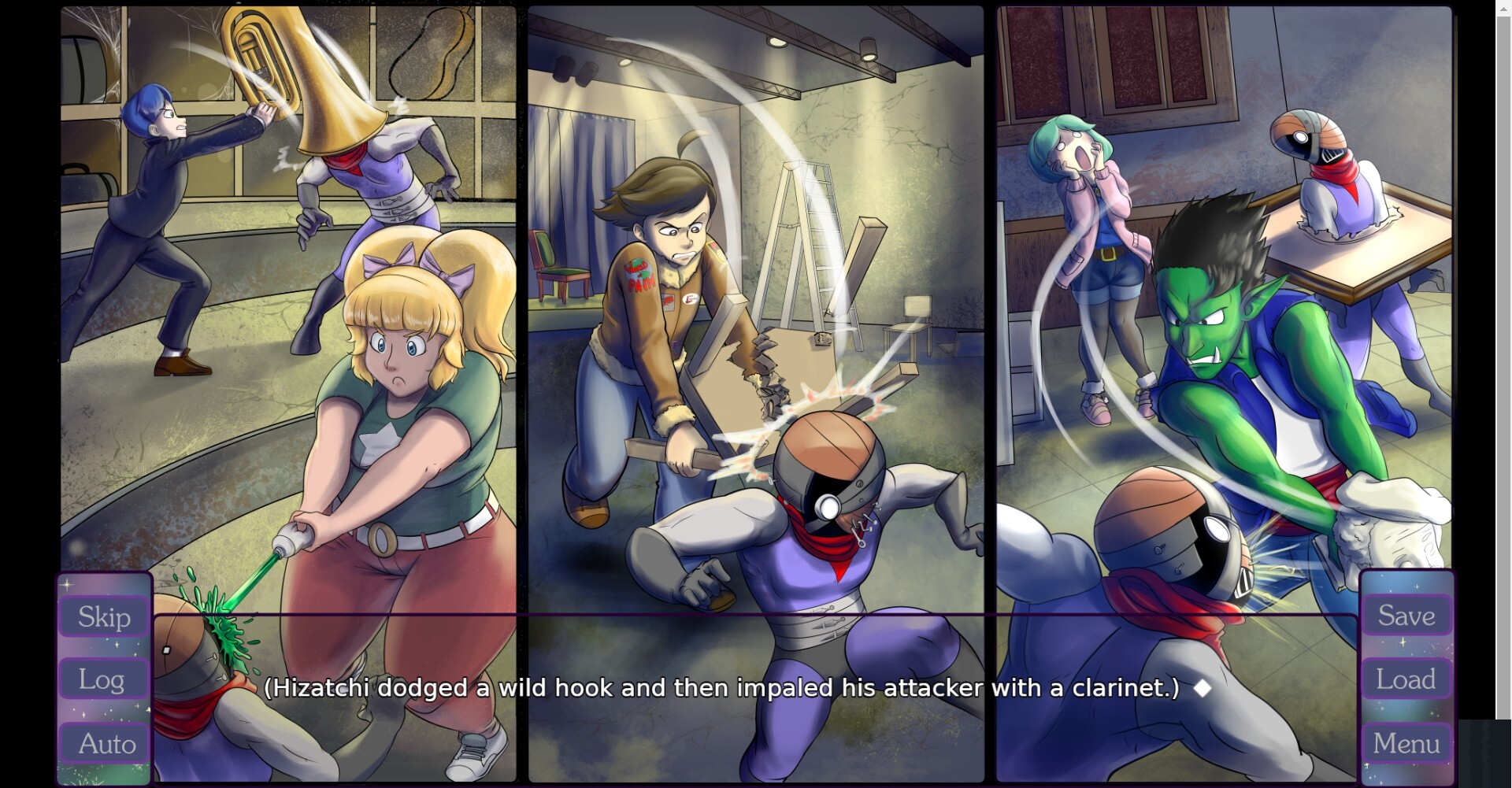

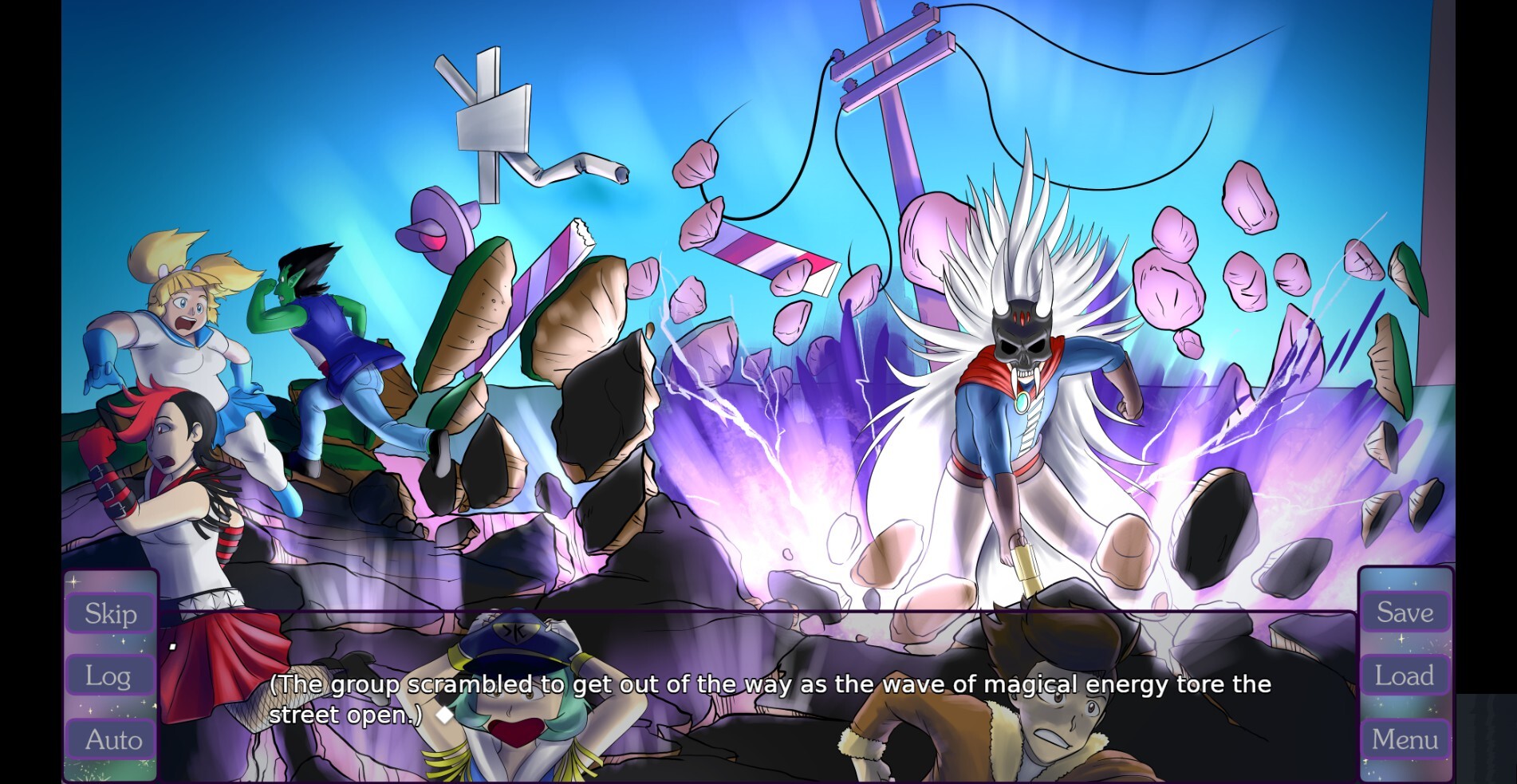

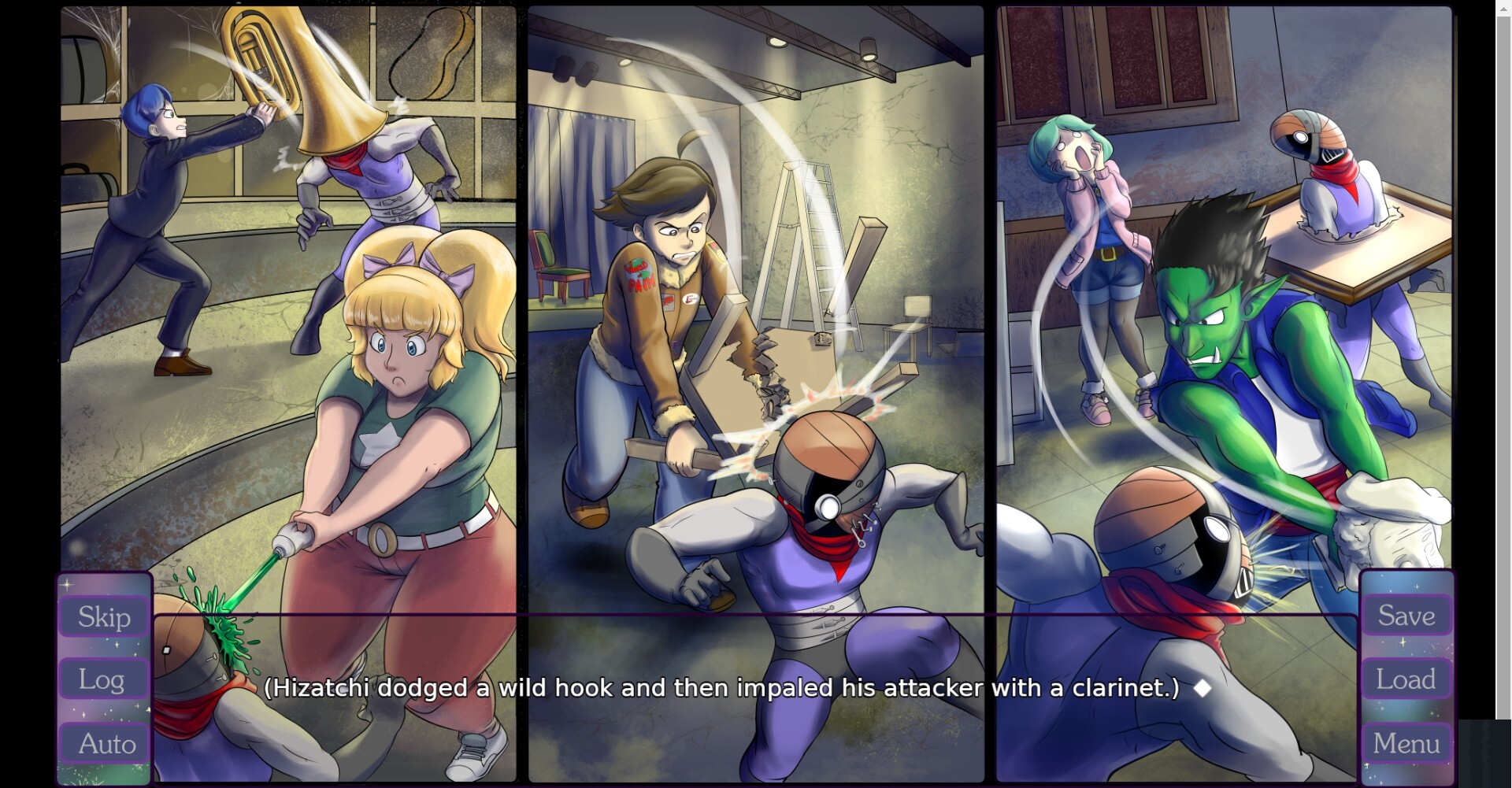

The other way that I feel MDF compensates for what may be seen as a weaker art style is almost sheer brute force; bombarding the audience with visuals. While the game features a lot of the talking head style of presenting dialogue, it also makes frequent of use of splash screen illustrations during moments of physical comedy or especially fighting scenes. These are often less for spectacle and more to allow the player to more quickly understand and engross themselves in the actions happening rather than relying on purely description; effectively, it gives the game the rhythm of animated or live action media, having spontaneous gags and combat with moment-to-moment ups and downs. Even in calmer moments, we sometimes get illustrations just to keep the presentation feeling dynamic and to keep the reading from wearing on us.

Of particularly note are the animated transformation sequences, which evoke Sailor Moon's iconic transformation sequence. These are the clear peak of the game's visual spectacle, which reads to me like it's recognizing how critical those sequences are to the magical girl genre's identity. If only one thing in the game could be animated, the transformations are the most natural choice.

While we're talking about the visuals, I feel like I have to note that MDF really understood that the monster designs in Super Sentai and its ilk are meant to be first and foremost weird. There's no real theme to them that I can identify, there's no real consistent emotion they're meant to evoke, but setting the silly next to the intimidating and the inhuman next to the completely human emphasizes that they're just an odd bunch and helps the individual monsters stand out.

The music in the game seems to be prioritizing a functional sound that serves the narrative needs of the moment rather than a strong sense of musical identity on the game's whole, to the point that I initially got the idea in my head that it might be using premade music asset packs - although to be clear, I've been given clarification that it's all original music, and seeing the names directly in the credits did suggest to me that I had misunderstood when I was playing. That is to say, it would be hard to get me to claim that a particular track sounds like it comes from MDF: Magical Defense Force in the same way that something might make me think "this sounds like something from EarthBound" or "this sounds like something from Hotline Miami". The largest part of the game, the calmer and dialogue-driven segments, do tend to feature inoffensive mood music. The first thought that came to my head why trying to think of a comparison was Trauma Team, but I'd imagine most people would take it as trying to feel like Ace Attorney if anything.

In fact, the main strength of the music of this game is how it enhances various scenes through its wide variance in moods. The music is light when not much is happening, the music is eerie when a new enemy has shown themselves, the music pumps you up when the fighting is underway. The game can ask you to treat it as a joke and then ask you to treat it seriously without either being to the detriment of the other because the music clearly delineates the severity in which we're expected to approach it at any given moment. Considering that this is a much lauded aspect of the Ace Attorney series, how that series is one of the most internationally renown visual novels, and how many indies openly draw from it, I suspect that MDF: Magical Defense Force also took note of how Ace Attorney's presentation worked and tried to make use of that knowledge.

This might seem like a non sequitur, but the laptop that I had initially played this game on and typed all my notes in physically fell apart when I was trying to finish this review, which delayed me posting this thread by a few months even though I had safely stored my notes in somebody else's DMs. But I'm glad to report that those initial notes became a little bit outdated as a result. I had a planned to include a section on my biggest complaint about the game and provided some apologia for the game in response to that issue; essentially, there was an early scene which accidentally set the wrong expectations for the game, specifically making the game seem like it might end going in a pornographic or exploitative direction. So as I played through the game and it gradually resolved that confusion I felt that I should explain why the game wasn't what that scene led me to imagine, but it seems that before I had the opportunity to say anything the developers realized that this scene wasn't reading the way that it was supposed to, and so fixed it themselves.

So after making a whole big section in my notes in response to this one major complaint, I don't even have to make that complaint anymore. Still, I did describe some aspects of the game in this section of my notes, so I may as well go into this anyway. Essentially, the idea as I understood it was that the game predicted that the player associated visual novels, and perhaps games in a similar area aiming for an anime aesthetic with prominent female characters, as primarily pornographic in nature. To prey on that player's expectation, the story of the game sometimes seems to approach that, but then the titillation that it seems to be promising just isn't what happens.

The biggest component of this is that MDF has a setup which, described in broad strokes, has some resemblance to a harem anime. The harem genre gives you a central male character who is the audience analogue and a bunch of prominent female characters who are treated like food items at a buffet to sample and decide between, and you have a premise that forces them together. Whether the main character enjoys this situation or would rather be left alone, he is at the center of this female attention so that the audience can project themselves into the story and enjoy the fantasy of receiving that attention. In MDF: Magical Defense Force, while Frank has a number of women thrust into his life that he's forced to interact with, a lot of them don't seem that interested in him whatsoever, not even enough to draw their comic ire. They aren't necessarily good friends or intense rivals, they're just people in his life who weren't there before. Frank enters a magical world where a group of women are at the center, but despite being the central character of our story, as far as I've gotten to, that world never shifts to match and leaves him at the periphery.

As far as romance goes, at the risk of spoilers, I'm not even sure if that's ever going to be an element in this. It isn't in the chapters that I played. There are a few characters who are closer than others such that they're in a position that the relationship could easily be revealed to have an underlying romantic foundation; for example, the lead character Michiki does tend to cling to Frank and seems very friendly towards him. But her claim is that she's sticking to him because she thinks he's valuable support in her adventure, and there isn't anything that I can think of which calls that into question. Despite his protests, he does prove to be a useful resource for her both in and out of battle, and while she's perhaps the friendliest character towards him, we also see that she's also very friendly to everyone else.

With that harem-esque setup in mind, I was also pleasantly surprised by how much I liked the various male characters in MDF. Harem works that are very targeted at a straight male audience will often tend to have very little male presence beyond the main character and maybe a friend to help him get into mischief, because why would you add a male character when you could be adding another woman to the harem to increase the titillation factor? Even if it's an action work where the women are physically capable, there might be an aspect to the premise that declares that only women can fight so that they can continue to receive the focus. In MDF: Magical Defense Force, when a fight breaks out, everyone fights together. Everyone gets a cool moment. Even though it's the magical girls who are the center of the story, there are a bunch of other non-magical characters who also contribute. Since this isn't really a story about a female experience in the way of magical girl series made by women and aimed at aimed at girls and so has no special justification for an overwhelmingly female cast, it strives for equality instead, making everyone seem more competent because they can share the floor with other competent people.

Tangentially, it occurs to me that this game should probably comfortably pass the Bechdel test. The main story less so, I suppose; with Frank being the main character, he's still going to be present in a large number of scenes, but since he's not driving the story they're probably not focusing on him when he's no longer in the room. Either way, I'm confident that it would at least be achieved through the extra scenarios, which focus on interactions between pairs of characters without Frank involved them, and only a few of them including the other boys.

I will say, though, that there are a few times that the art strikes me as a little fetishized, particularly around Michiki. It's rare, to the point that I feel like it might simply be due to there being a high enough quantity of artwork and me being kind of on guard when I was playing so there was just enough white noise to catch my ear. There's also a few things that are clearly more intentional like the villain tending to be presented as having sexier outfits than the heroines but that's following in line with a trope you'd see in Sailor Moon, and there's one character who has a Daisy Duke sort of outfit but I feel like that's probably meant at least in part to evoke car culture or Americana aesthetics. Honestly, I feel that if there's anything worth criticizing in this regard, I'm not going to be the person who is best equipped to make that criticism. The thought entered my head but if you look at the art and judge it for yourself it's going to be as valuable as anything I could say.

With what would have been my biggest complaint out of the way, I now have to bump up what would have been my second biggest complaint, which really isn't much of a thing either. That is, the ending of the set of the episodes I played was a little weak. In fairness, it really can't have a great ending, since this is just the first set of episodes in an episodic story, so it obviously can't be expected to resolve the main story entirely. But even with that in mind, despite building to a fine climax there's no particular point of story progression that it stops on, so reaching the end of this particular set of chapters just feels like it stops arbitrarily rather than closing out a first act. I probably won't care about this at all once I get to the end of the full story, but I just wonder if this might be handled a little more elegantly.

I'd like to conclude this review by describing my main feeling towards MDF: Magical Defense Force, the central appeal drawing you into this experience. Put simply, I enjoy it for how authentic it is. Specifically, how authentic it is as a work styling itself after the magical girl genre and other kinds of Japanese superhero fiction. It's a comedy, but it doesn't feel like it's mocking the magical girl concept or anime tropes even as it plays with them.

As part of that, despite it being primarily a comedy, I like how the tone shifts around according to the situation. When the monsters appear and the heroes have to fight them, it's their lives on the line, and so as the severity of the danger they face increases so does the severity that they face it with. Some of the stronger opponents they face genuinely exude a ferociously intimidating presence and provide the sense that managing such powerful threats is an ordeal requiring real effort and pain. There is actual bloodshed at times, which might be cartoonish, but it doesn't feel like a joke. Michiki tends to end a battle with a signature move that leaves the enemies physically broken, giving a clear end to the danger and providing a sense of relief from the tension in classic Japanese superhero fashion. The game is built to push you to the edge of your seat at one minute, then make you laugh at the next.

Naoko Takeuchi did not create Sailor Moon in a vacuum. She looked at existing works like La Belle Fille Masquée Poitrine and Super Sentai, taking elements of those as she wishes, and arranged them with her own thoughts and ideas to create something that feels like it stands on its own, not requiring those previous works to function. I feel that MDF: Magical Defense Force is attempting to do something very similar; the authenticity does not draw simply from how closely it follows the source material, but from how intentionally it chooses to deviate from the source material, tapping into perhaps familiar ideas of American suburban malaise and the struggle to develop healthier attitudes in how one relates to other people. The sense it projects is that it's the work of people who grew up on Sailor Moon, Super Sentai, and other Japanese media and simply want to participate, to take inspiration from things they love and create something unique from them.

As a necessary preface, I didn't stumble on this game at random. I'm a member of a Discord server with one of the developers, and perhaps due to shared interests, he gifted me the first set of chapters of this game. I wasn't asked for feedback and I don't think he was even that aware that I also frequent ResetEra, but if I'm given a gift, I figure that it's polite to give something in return, and the least I can do is provide a review. This isn't meant to be just an ad for the game, so I'm going to try to really sink my teeth in while remaining even-handed in describing its strengths and weaknesses, but it's probably worth bearing in mind how it might affect what I'm comfortable with saying.

I wanted to start us off with a little history lesson regarding the magical girl genre and some discussion of my own experience with it so that we can all approach MDF with a similar baseline of understanding, but it's going to add a significant chunk of reading to what I expect to be an already article-length OP, so I'm going to put in spoiler tags. Feel free to read it if you're interested in the genre in general, or else we can proceed straight to the game review.

The magical girl genre begins in the 1960s, at a time when manga was still very much a male-dominated industry, even when aiming for a female audience. Specifically, its origins are often credited to the American sitcom Bewitched, which I imagine you may already be familiar with since it was popular in reruns for a long time; it revolves around a witch with seemingly limitless powers who tries to live as a normal mortal American housewife, but frequently ends up both causing problems and getting out of them through the use of her magic. The first magical girl manga, Himitsu no Akkochan, actually predates Bewitched by a few years despite the author giving it credit – it's possible that he was confusing it with an earlier American movie, I Married a Witch – but the first animated take on the genre, Sally the Witch, debuted not long after the Japanese dub of the show. With Sally's success, Akkochan also received an animated adaptation inheriting its time slot, and magical girl anime secured a constant presence.

It's worth noting that much like Bewitched, magical girls of this era were more in line with comedies featuring powerful main characters dealing largely with everyday life. While it's possible that the protagonist might get into fights, comedy rather than action was the major focus of the story, and there wasn't a strong consistent villainous presence to oppose the hero. This classical style of magical girl series never went away, but it's rarely attained a big international presence, including in English-speaking territories.

In the 1970s, transforming human-scale superheroes were popularized in Japan by series such as Kamen Rider and Super Sentai, often having the hero fighting back against some kind of evil organization. As a result, there was an increasing number of series which combined magical girls with this format. The earliest one I'm aware of is Love! Love! Witch Teacher, originally a comedic magical girl live action series by the creator of Kamen Rider which then changed gears partway through and had its protagonist transform into a superheroine by the name of Andro Mask. Cutey Honey is often viewed as a magical girl superhero series, although it was aimed at boys and contained a lot of the titillation that its creator was making his career on. At the same time, women were making huge strides in manga aimed at girls, often pushing them into more dramatic territory with heavier themes. However, the magical girl genre was not driven by female creators at this time to my knowledge.

The 1980s the genre apparently experienced another wave of popularity, perhaps influenced by idol entertainers being at the height of their own popularity and expanding the interest in female-led series to male audiences. The end of the decade included remakes of both Himitsu no Akkochan and Sally the Witch, and it also led to a new series of live action transforming superhero magical girl shows spearheaded by Kamen Rider's creator starting with Magical Chinese Girl Pai Pai!. But I'm more interested in heading over to the 1990s. At the start of the decade, Magical Chinese Girl Pai Pai! received an even more popular successor, La Belle Fille Masquée Poitrine. It's shortly after Poitrine finished airing that Naoko Takeuchi used it for the basis of her manga Codename: Sailor V, which was then mixed with elements of Super Sentai to become Sailor Moon.

The influence of Sailor Moon cannot be overstated. Beyond simply being an extremely popular magical girl series even beyond its primary target audience, it was part of the early wave of English-translated anime that pushed anime into mainstream children's entertainment in English-speaking territories. As a result, it's often internationally the face of the magical girl genre as a whole, if not one of the faces of anime itself for quite some time; when the magical girl genre is in discussion, it's often Sailor Moon specifically that people imagine. The transformation sequence is itself iconic, frequently subject to imitation and tribute.

While it's by far the biggest, Sailor Moon wasn't the only popular magical girl series to come out of the nineties; I think in general, it's the period where women starting taking more control over the genre. In later decades, dark or subverted magical girl media seems to have also become a popular trend, such as Puella Magi Madoka Magica. But the evolution that led us to Sailor Moon is what I'm most interested in for this discussion, since I believe that Sailor Moon is also the biggest influence for the game we'll be looking at.

For me personally, I'd usually say that I'm a mecha nerd rather than a general purpose anime nerd, so while I'm aware of a lot of this on paper, my actual viewing history for magical girl media is pretty shallow. Aside from watching a certain amount of Sailor Moon, I did enjoy Cardcaptor Sakura, which I believe is a little more in line with the older style, as well as an example of how magical girl media in the nineties was being more driven by female creators. I've also had a certain amount of exposure to Magic Knight Rayearth by the same creators.

Aside from that, I've bumped into a bunch of magical girl stuff where it aligns more with the stuff that I normally watch, but those are generally more aimed at a male audience and often feel more exploitative. I was recommended the original Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha back in the day, which was intended as an action-focused series that styles itself after Gundam. Maybe later series in the franchise are better, but the first one had a lot of panty shots and changing scenes and things like that, which coupled with Nanoha's flat and unblemished personality read as very fetishistic to me. The earlier Galaxy Fräulein Yuna was a similar concept, being inspired by the MS Girl design motif that reimagines the Mobile Suits from Gundam as costumes. It seemed to be to be more inoffensive, but also very shallow, feeling like a showcase for cute designs without much interest in developing characters to go with them. Dangaizer 3 was a late entry in the wave of retro mecha OVAs in the eighties and nineties, differentiating itself by also being an early dark magical girl story with skimpy costumes and a heavy focus on sex appeal.

Because of stuff like this, I tend to be more apprehensive to magical girl works by male creators and which seem to be focused on a male audience; my major concern is that the characters are meant more to be looked at by the audience than to be seen as humans which can be related to.

As we proceed into the review of this game, hopefully this gives an idea of how I'm trying to contextualize the game and what the pitfalls are that I'm watching out for.

The basic premise of MDF: Magical Defense Force begins with Frank, the antisocial and truant student who serves as our main character, finding himself using improvised weapons to assist a bubbly magical girl named Michiki in a battle with a monster. Despite his protests, Michiki then forcibly intrudes into Frank's life, insisting that they work well together. While the story primarily follows Frank, Michiki, and their friends as they fight against different monsters every episode and try to assemble their full magical girl team, we also have frequent glimpses of the mysterious evil organization conspiring against them led by Mary-Anne, who often seems less outright evil but more cranky and disrespectful to her subordinates.

I imagine that anyone who grew up with Sailor Moon would already start seeing how this might feel like it's modeling itself off of that series. Michiki fits with Sailor Moon herself, the leader of the team who is a bit of a doofus but still a capable hero. The team resembles the Sailor Senshi, including that part of the quest is to assemble them rather than the team being assembled all at once. Mary-Anne maps up to Queen Beryl, who we frequently see scheming against the Sailor Senshi early in the series, perhaps the series' villains in general.

But in part these connections often map up to the standard roles in Super Sentai or similar works that Sailor Moon was also working off of, and there are also things missing or elements that don't really line up well to anything in Sailor Moon. As the player continues through the game, the semblance feels thinner. In fact, part of the reason why I connect MDF so much to Sailor Moon is that a lot of the tropes that it adopts or plays with aren't specific to the magical girl genre, but are present in Super Sentai and other Japanese superhero works; it might even evoke those harder than it does with magical girls. It ultimately comes across less that the game is trying to be understood as a response to Sailor Moon and more that it uses it as a structural reference point which it can then deviate from as desired.

Frank doesn't do anything more extreme than flipping the bird constantly and using gendered insults, but he's still very much a negative character; he spends much of the time complaining or picking fights with others, including people who are friendly to him. It's easy to imagine that this sort of character could end up being sincerely unlikable to the detriment of the story as a whole, but it's balanced out in two ways. The more commonly seen factor is that, with him being the protagonist of a comedy, Frank is constantly punished rather than allowing us to dwell on his negativity. While he's a contributing member of the team, he gets dunked on too often to make us feel that the game wants us to see him as the coolest one.

The other thing is that the game establishes quickly that the trajectory this story will follow is most likely going to be a journey of personal growth and redemption for Frank. The first episode has a framing device where he's telling the story to a therapist, which already puts things through the lens of reflecting on what his life is like and how it can be improved. While the spotlight is primarily given to the magical girls' battle against evil, Frank's development is still occasionally brought up, suggesting that it's going to be an overarching point that will culminate as the story progresses. That this all comes up because of the more optimistic Michiki evokes a particular trope which I imagine there's a lot written on, but I personally feel like I relate strongly to the idea of having your life benefit from having strong relationships with women such as friends and family, and I think it's written in a way that the magical girls' adventure feels like something that exists independently and is important without Frank even if he benefits from being included in it.

The characters may at least at first feel a little shallow, which I suspect is in part due to MDF's story demands and writing needs. Because of the comedy focus of the game, characters are often established as comedic devices first and foremost, being more of a gimmick that can be described in a word than seeming like they're complex people who are built out of their personal histories. That said, little dramatic moments throughout the game do slowly build some of the characters up over time. There are also extra scenarios included in the game - short optional stories that don't really matter to or fit into the main plot - which serve largely to show off interactions between characters that aren't explored as much or just to provide more opportunity to flesh the characters out. These are very short scenes, so none of these scenes are too exciting; I'd say my favourite of them has the punk girl Hoshune chew out wacky conspiracy theorist Lee for his failure to recognize real government abuse.

The leader of the magical girls, Michiki, strikes me as a particularly strong example of how the nature of the story affects how the characters are written. Looking at Sailor Moon functionally, Usagi is a layered character because she's the audience's viewpoint character; she's the one who is closest to us in the audience in how she understands the story, and who we are most expected to project ourselves into to engross ourselves in the story. Transforming magical girls have often represented transition to adulthood, such as Marvelous Melmo or Minky Momo using magical means to physiologically transform from girls to women. Usagi instead represents that thematically through the distinct layers in her personality, her normally possessing the negative traits that we tend to see in ourselves such as clumsiness, laziness, and stupidity, but through becoming Sailor Moon being able to reach her potential and express her capacity for strength, confidence, and grace. In MDF: Magical Defence Force, it's instead Frank that's the viewpoint character and who expresses the negative traits, not Michiki. Michiki as a function instead better resembles Sailor Moon's Luna, the character who serves as our link with the fantasy world, providing our information about how it works and what our mission is. She already starts off expressing a level of competence, so while she also tends to be clumsy, her flaws aren't as sharply delineated from her strengths.

Trying to think of my favourite character, I feel like the game's attempt to gradually build its characters up becomes visible. An early favourite of mine is Uli, the long-suffering monster maker. He feels very much like a Super Sentai character concept, similar to Pleprechaun from Zyuranger, but the game gets a lot of humour of pushing him more into the foreground rather than having him as just a background fixture to justify the existence of the monsters. But as the story continues, I gravitated more towards Hizatchi, Frank's best friend. He seems very stoic and even brutish, but the longer we spend to him the easier it is to notice that he's mostly seen helping others, and he's the character who seems more aware of others' emotions while also feeling no hesitation in caring for them.

The setting of MDF doesn't quite seem to be our real world, even if it's similar. The country the story takes place in is a fusion of America and Japan similarly to how Los Angeles is depicted in the localized version of Phoenix Wright. While it's probably meant to be silly, it isn't a one-off gag, and when we hear the names of other countries, they also seem to be similar amalgams. It comes across less as purely riffing on questionable localization decisions and more a conscious adoption of the accidental awkwardness produced by that setting; because the setting is both America and Japan, it can use tropes seen in anime that come from the Japanese experience without having to call attention to them as abnormal, while it can also feature more American imagery and humour without breaking the cohesion. The characters appear to be college-aged, allowed to drive and allowed to drink, perhaps living with their parents but without visible supervision. The town they live in feels like a sleepy American suburban. However, their school experience appears to be more in line with Japanese high school, revolving around the homeroom rather than separate rooms by subject. Some characters wear Japanese school uniforms, but there's nothing to indicate that there are any rules encouraging them or that they're even worn specifically for school, so without any other acknowledgement it just comes across as a matter of personal fashion choice than anything else.

As a more subtle thing, while magic and monsters are clearly out of the ordinary, the characters in the game never seem to be phased by non-humans talking to them. The most obvious example of this is that Hizatchi, Frank's best friend, is clearly a hobgoblin. There are enough dropped opportunities to acknowledge this that makes me feel like it's a running gag, but hobgoblins don't really strike me as having anything to do with the magical girl genre or Super Sentai or other Japanese media that isn't specifically drawing off European fantasy, so I interpret it more as just a quirk of the game's setting. Presumably this is a world where non-humans with human-like intelligence are just things you see once in a way and aren't viewed as particularly notable in and of themselves by average people.

The art style reads to me as animesque rather than anime-styled, and not necessarily in a way that's intentional. That is to say, it feels to me that this is the sort of art style that results when someone learns from "how to draw anime" books or other resources which similarly attempt to reproduce the art styles seen in anime without the teacher having experience with its actual production. Perhaps the artist of the game might also still be fairly new and their skills are still in the development stage. I don't have anywhere even remotely close to the art knowledge or skill necessary to go into detail critiquing this aspect, but if you think about anime style as something related to animation, you can imagine how consistency would be mission critical to ensure visual continuity from frame to frame. Even between different characters, shape or proportion may trend towards similarity to make it easier for the artist to repeat them. That consistency isn't really visible here. At first glance, I wasn't too impressed with the art of the game; the style used isn't something I'd usually seek out.

This may sound like I'm tepid on the art in MDF, and that's largely true taking any given shot of it in a vacuum. However, I think the actual result you see on the whole is strengthened by the way that art style is utilized, to the point that I can't say it would be better for it to have a style more akin to what you typically see in television anime due to how much you'd lose. A few characters have details in their clothing that seem like they'd be a pain to animate; in particular, I'm struck by Frank's jacket being accessorized with a bunch of different slogans like the cheesy "World of PAIN" and "FU". Considering the decidedly non-uniform usage of Japanese school uniforms, it strikes me as providing an American cultural counterpoint, where more individual or cliquish personal fashion is on display even in school settings. Actually, when working on this thread, I learned that Sailor Moon's Naoko Takeuchi had originally intended the Sailor Senshi to have more individualized designs to reflect the individual personalities and tastes of the characters, which she felt was natural for girls, but those design elements were standardized development due to animation needs. It's interesting that MDF: Magical Defense Force's more individual costume design, while aiming for a simple sailor suit-inspired design much like Sailor Moon's, also has more individualized traits that might better reflect Takeuchi's original intent.

There's also a clear effort to include some diversity, both in ethnicity and body type, that we don't often see in anime trying to capture to the experience of an average girl in relatively ethnically homogeneous Japan. The most prominent example is Michiki, who is visibly chubbier than most of the other characters, which I feel is particularly surprising for the leading lady. The height of characters varies quite a bit as well, with the women not being shorter than the men with any great consistency. I also took notice of one design used to represent a few minor characters being a Sikh man, complete with kirpan and kangha; someone who doesn't look too far off from someone I might meet on an average day, but doesn't show up a lot in magical girl anime. I won't go as far as to claim that it's implemented well or poorly since that's more for the people depicted to say, I do think it would be nice to see ethnic variety from the major characters, but I think it at least demonstrates an interest in exploring more varied physical features in their designs than the source material tends to.

The other way that I feel MDF compensates for what may be seen as a weaker art style is almost sheer brute force; bombarding the audience with visuals. While the game features a lot of the talking head style of presenting dialogue, it also makes frequent of use of splash screen illustrations during moments of physical comedy or especially fighting scenes. These are often less for spectacle and more to allow the player to more quickly understand and engross themselves in the actions happening rather than relying on purely description; effectively, it gives the game the rhythm of animated or live action media, having spontaneous gags and combat with moment-to-moment ups and downs. Even in calmer moments, we sometimes get illustrations just to keep the presentation feeling dynamic and to keep the reading from wearing on us.

Of particularly note are the animated transformation sequences, which evoke Sailor Moon's iconic transformation sequence. These are the clear peak of the game's visual spectacle, which reads to me like it's recognizing how critical those sequences are to the magical girl genre's identity. If only one thing in the game could be animated, the transformations are the most natural choice.

While we're talking about the visuals, I feel like I have to note that MDF really understood that the monster designs in Super Sentai and its ilk are meant to be first and foremost weird. There's no real theme to them that I can identify, there's no real consistent emotion they're meant to evoke, but setting the silly next to the intimidating and the inhuman next to the completely human emphasizes that they're just an odd bunch and helps the individual monsters stand out.

The music in the game seems to be prioritizing a functional sound that serves the narrative needs of the moment rather than a strong sense of musical identity on the game's whole, to the point that I initially got the idea in my head that it might be using premade music asset packs - although to be clear, I've been given clarification that it's all original music, and seeing the names directly in the credits did suggest to me that I had misunderstood when I was playing. That is to say, it would be hard to get me to claim that a particular track sounds like it comes from MDF: Magical Defense Force in the same way that something might make me think "this sounds like something from EarthBound" or "this sounds like something from Hotline Miami". The largest part of the game, the calmer and dialogue-driven segments, do tend to feature inoffensive mood music. The first thought that came to my head why trying to think of a comparison was Trauma Team, but I'd imagine most people would take it as trying to feel like Ace Attorney if anything.

In fact, the main strength of the music of this game is how it enhances various scenes through its wide variance in moods. The music is light when not much is happening, the music is eerie when a new enemy has shown themselves, the music pumps you up when the fighting is underway. The game can ask you to treat it as a joke and then ask you to treat it seriously without either being to the detriment of the other because the music clearly delineates the severity in which we're expected to approach it at any given moment. Considering that this is a much lauded aspect of the Ace Attorney series, how that series is one of the most internationally renown visual novels, and how many indies openly draw from it, I suspect that MDF: Magical Defense Force also took note of how Ace Attorney's presentation worked and tried to make use of that knowledge.

This might seem like a non sequitur, but the laptop that I had initially played this game on and typed all my notes in physically fell apart when I was trying to finish this review, which delayed me posting this thread by a few months even though I had safely stored my notes in somebody else's DMs. But I'm glad to report that those initial notes became a little bit outdated as a result. I had a planned to include a section on my biggest complaint about the game and provided some apologia for the game in response to that issue; essentially, there was an early scene which accidentally set the wrong expectations for the game, specifically making the game seem like it might end going in a pornographic or exploitative direction. So as I played through the game and it gradually resolved that confusion I felt that I should explain why the game wasn't what that scene led me to imagine, but it seems that before I had the opportunity to say anything the developers realized that this scene wasn't reading the way that it was supposed to, and so fixed it themselves.

So after making a whole big section in my notes in response to this one major complaint, I don't even have to make that complaint anymore. Still, I did describe some aspects of the game in this section of my notes, so I may as well go into this anyway. Essentially, the idea as I understood it was that the game predicted that the player associated visual novels, and perhaps games in a similar area aiming for an anime aesthetic with prominent female characters, as primarily pornographic in nature. To prey on that player's expectation, the story of the game sometimes seems to approach that, but then the titillation that it seems to be promising just isn't what happens.

The biggest component of this is that MDF has a setup which, described in broad strokes, has some resemblance to a harem anime. The harem genre gives you a central male character who is the audience analogue and a bunch of prominent female characters who are treated like food items at a buffet to sample and decide between, and you have a premise that forces them together. Whether the main character enjoys this situation or would rather be left alone, he is at the center of this female attention so that the audience can project themselves into the story and enjoy the fantasy of receiving that attention. In MDF: Magical Defense Force, while Frank has a number of women thrust into his life that he's forced to interact with, a lot of them don't seem that interested in him whatsoever, not even enough to draw their comic ire. They aren't necessarily good friends or intense rivals, they're just people in his life who weren't there before. Frank enters a magical world where a group of women are at the center, but despite being the central character of our story, as far as I've gotten to, that world never shifts to match and leaves him at the periphery.

As far as romance goes, at the risk of spoilers, I'm not even sure if that's ever going to be an element in this. It isn't in the chapters that I played. There are a few characters who are closer than others such that they're in a position that the relationship could easily be revealed to have an underlying romantic foundation; for example, the lead character Michiki does tend to cling to Frank and seems very friendly towards him. But her claim is that she's sticking to him because she thinks he's valuable support in her adventure, and there isn't anything that I can think of which calls that into question. Despite his protests, he does prove to be a useful resource for her both in and out of battle, and while she's perhaps the friendliest character towards him, we also see that she's also very friendly to everyone else.

With that harem-esque setup in mind, I was also pleasantly surprised by how much I liked the various male characters in MDF. Harem works that are very targeted at a straight male audience will often tend to have very little male presence beyond the main character and maybe a friend to help him get into mischief, because why would you add a male character when you could be adding another woman to the harem to increase the titillation factor? Even if it's an action work where the women are physically capable, there might be an aspect to the premise that declares that only women can fight so that they can continue to receive the focus. In MDF: Magical Defense Force, when a fight breaks out, everyone fights together. Everyone gets a cool moment. Even though it's the magical girls who are the center of the story, there are a bunch of other non-magical characters who also contribute. Since this isn't really a story about a female experience in the way of magical girl series made by women and aimed at aimed at girls and so has no special justification for an overwhelmingly female cast, it strives for equality instead, making everyone seem more competent because they can share the floor with other competent people.

Tangentially, it occurs to me that this game should probably comfortably pass the Bechdel test. The main story less so, I suppose; with Frank being the main character, he's still going to be present in a large number of scenes, but since he's not driving the story they're probably not focusing on him when he's no longer in the room. Either way, I'm confident that it would at least be achieved through the extra scenarios, which focus on interactions between pairs of characters without Frank involved them, and only a few of them including the other boys.

I will say, though, that there are a few times that the art strikes me as a little fetishized, particularly around Michiki. It's rare, to the point that I feel like it might simply be due to there being a high enough quantity of artwork and me being kind of on guard when I was playing so there was just enough white noise to catch my ear. There's also a few things that are clearly more intentional like the villain tending to be presented as having sexier outfits than the heroines but that's following in line with a trope you'd see in Sailor Moon, and there's one character who has a Daisy Duke sort of outfit but I feel like that's probably meant at least in part to evoke car culture or Americana aesthetics. Honestly, I feel that if there's anything worth criticizing in this regard, I'm not going to be the person who is best equipped to make that criticism. The thought entered my head but if you look at the art and judge it for yourself it's going to be as valuable as anything I could say.

With what would have been my biggest complaint out of the way, I now have to bump up what would have been my second biggest complaint, which really isn't much of a thing either. That is, the ending of the set of the episodes I played was a little weak. In fairness, it really can't have a great ending, since this is just the first set of episodes in an episodic story, so it obviously can't be expected to resolve the main story entirely. But even with that in mind, despite building to a fine climax there's no particular point of story progression that it stops on, so reaching the end of this particular set of chapters just feels like it stops arbitrarily rather than closing out a first act. I probably won't care about this at all once I get to the end of the full story, but I just wonder if this might be handled a little more elegantly.

I'd like to conclude this review by describing my main feeling towards MDF: Magical Defense Force, the central appeal drawing you into this experience. Put simply, I enjoy it for how authentic it is. Specifically, how authentic it is as a work styling itself after the magical girl genre and other kinds of Japanese superhero fiction. It's a comedy, but it doesn't feel like it's mocking the magical girl concept or anime tropes even as it plays with them.

As part of that, despite it being primarily a comedy, I like how the tone shifts around according to the situation. When the monsters appear and the heroes have to fight them, it's their lives on the line, and so as the severity of the danger they face increases so does the severity that they face it with. Some of the stronger opponents they face genuinely exude a ferociously intimidating presence and provide the sense that managing such powerful threats is an ordeal requiring real effort and pain. There is actual bloodshed at times, which might be cartoonish, but it doesn't feel like a joke. Michiki tends to end a battle with a signature move that leaves the enemies physically broken, giving a clear end to the danger and providing a sense of relief from the tension in classic Japanese superhero fashion. The game is built to push you to the edge of your seat at one minute, then make you laugh at the next.

Naoko Takeuchi did not create Sailor Moon in a vacuum. She looked at existing works like La Belle Fille Masquée Poitrine and Super Sentai, taking elements of those as she wishes, and arranged them with her own thoughts and ideas to create something that feels like it stands on its own, not requiring those previous works to function. I feel that MDF: Magical Defense Force is attempting to do something very similar; the authenticity does not draw simply from how closely it follows the source material, but from how intentionally it chooses to deviate from the source material, tapping into perhaps familiar ideas of American suburban malaise and the struggle to develop healthier attitudes in how one relates to other people. The sense it projects is that it's the work of people who grew up on Sailor Moon, Super Sentai, and other Japanese media and simply want to participate, to take inspiration from things they love and create something unique from them.

Last edited: