And who brought dictatorship to Cuba?

-

Ever wanted an RSS feed of all your favorite gaming news sites? Go check out our new Gaming Headlines feed! Read more about it here.

Socialism and human nature

- Thread starter Spinluck

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Humans will destroy themselves if the world doesn't.

But that doesn't mean we can't strive to be better.

There will never be utopia -- no real practical avenue to a world without scarcity. That, I think, is not possible without the proper technology.

But there can be a unifying and identifying culture, set of cultures. There can be a road to socialism, even if it is never reached. There can be understanding. There can be the warmth of viability in a fundamentally meaningless world.

Okay, time to fess up; as a misanthrope, yes, I see the worst in all of us. Yes, nature, human nature, is destructive when unmoderated. It is shallow. It is primal.

That is the beauty of resistance. Goodness is not easy; it is not always default. Sharing, caring, unionizing, representing, anti-materialism -- these are easy to learn for many, nearly impossible to master for even more, including said many.

But resisting nature, resisting death, resisting oppression and injustice most of all -- that is, paradoxically, in our nature as well.

Flip the coin.

But that doesn't mean we can't strive to be better.

There will never be utopia -- no real practical avenue to a world without scarcity. That, I think, is not possible without the proper technology.

But there can be a unifying and identifying culture, set of cultures. There can be a road to socialism, even if it is never reached. There can be understanding. There can be the warmth of viability in a fundamentally meaningless world.

Okay, time to fess up; as a misanthrope, yes, I see the worst in all of us. Yes, nature, human nature, is destructive when unmoderated. It is shallow. It is primal.

That is the beauty of resistance. Goodness is not easy; it is not always default. Sharing, caring, unionizing, representing, anti-materialism -- these are easy to learn for many, nearly impossible to master for even more, including said many.

But resisting nature, resisting death, resisting oppression and injustice most of all -- that is, paradoxically, in our nature as well.

Flip the coin.

Last edited:

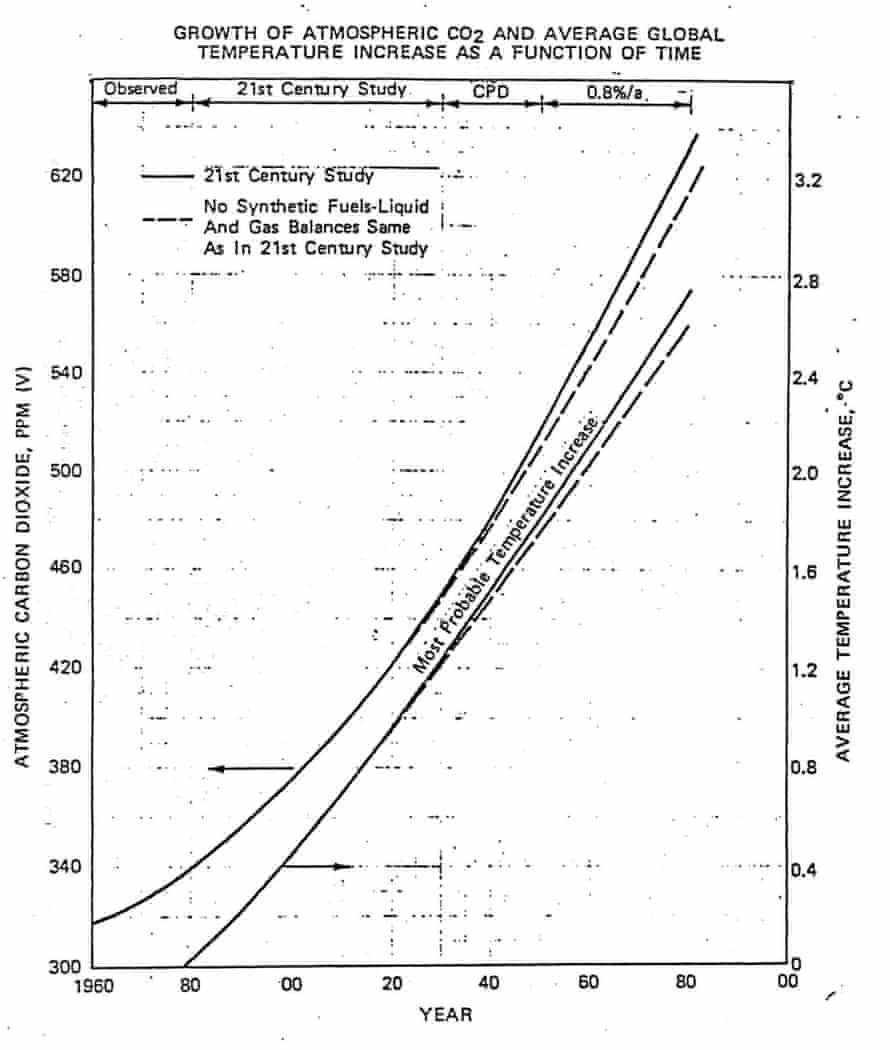

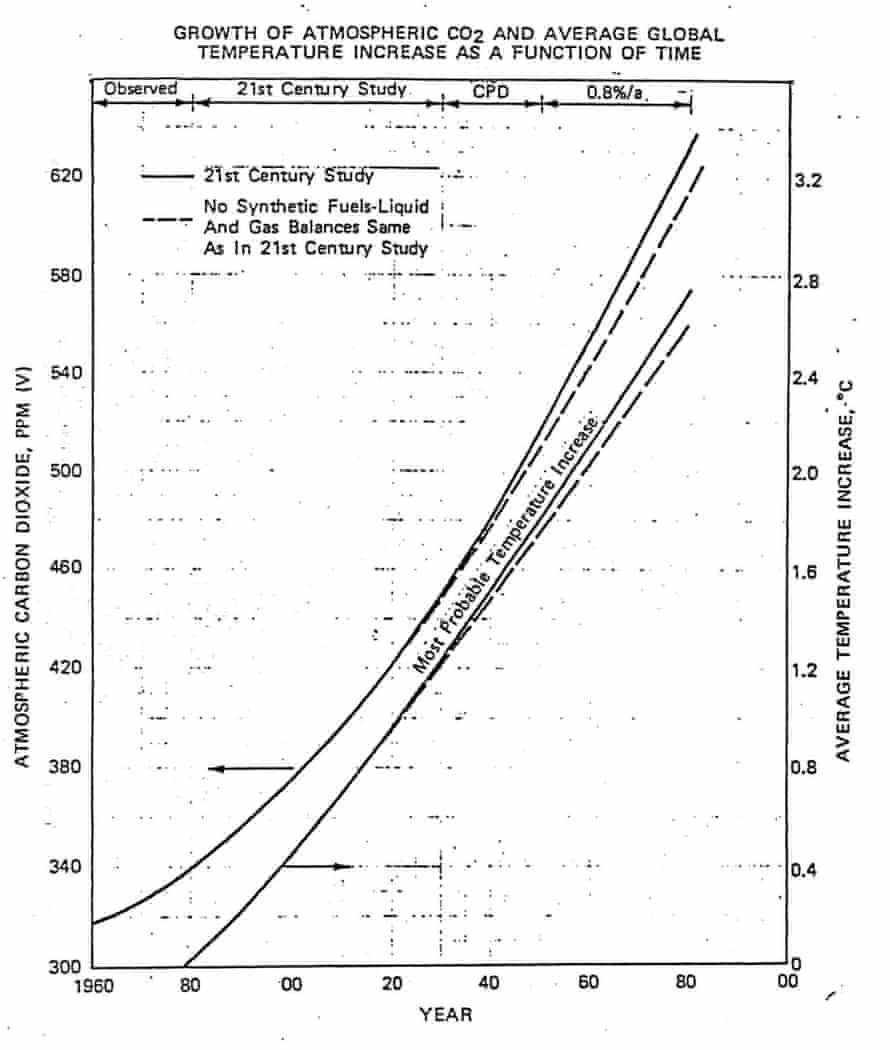

Exactly: That puts he US being as the main culprit of climate change, and still, you diminish every other (capitalist!) country contribution to do better as "not enough" and "there isn't a participation trophy for that".

Isn't it easier to admit that the US is just doing things the wrong way? Blame the system if you want to, but it really is HOW you led the system to be the way it is today, because everyone else is doing something different.

You mean all those political adventures done specifically to spread capitalism across the planet? Those political adventures??? Yeah I agree they were pretty horrible.

That's what happens when you let corporations dictate your laws, and let the military branch do what they please. Nothing to do with an economic system

That's what happens when you let corporations dictate your laws... Nothing to do with an economic system

???

Oh I see, yeah that's a fair point.Yeah I agree that claiming "capitalism is the natural order of things" is dumb. I was just responding to your claim that "capitalism isn't natural". I basically think all economic/political/social systems are rooted in various aspects of human nature. Claiming one is more natural than the other, or that one is totally unnatural, makes no sense to me.

TL;DR:

Social democracy: Top-down businesses, employers own the equity, call the shots, employees obey

Socialism: Bottom-up businesses, workers are partners, share in equity, democratize directions

If you don't understand this distinction (and in fairness most people don't), you will have a hard time talking cogently about socialism. The question of "who owns?" was the original reason the social democrats split from the orthodox socialists back in the 20th century. Socdems said "bosses should own" and socialists said "workers should own" and that is how we ended up where we are today.

Good stuff all around, but I'm interested in your thoughts about this Marx statement:

What, then, constitutes the alienation of labor?

First, the fact that labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind.

The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home. His labor is therefore not voluntary, but coerced; it is forced labor.

...

For as soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape.

He is a hunter, a fisherman, a herdsman, or a critical critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Can this view work for an updated society? Rhetorical question because it definitely can and does, but the examples Marx uses aren't relevant for a lot of people these days, so some might balk at it. Is there a nice easy way to update the examples here or come up with some other scenarios that can help 21st century folks living in a service based society like ours?

Because this aspect of socialism is often the one seen as a pipe dream, and why we typically hear all these "human nature" arguments as to why it's a waste of time to even talk about. Cause apparently human nature means resigning ourselves to a system built by and catered to as few as possible. It's human nature to expect less for more work done, and where most of the profits of that work don't go into yourself or the community but to a few individuals owners.

That's what happens when you let corporations dictate your laws, and let the military branch do what they please. Nothing to do with an economic system

You one of those types that thinks militaries are there to "protect freedoms" and such? They ensure the capital of the state. They're enforcers. So in a more capitalist state like America where the desire is to increase the profits of private interests, then that's what the military will be doing. And that's why it's very much tied to the economic system of a country.

For a different way of thinking about it beyond just the USA being a unique bad case, then consider the common retort to Nordic countries.

"Oh, it's nice to have socialism in your country, but if you had a proper military that didn't rely on USA and other imperialist powers on your side then you'd be dancing to a different tune!"

How many times have you heard that, or may have even repeated it? That's making a direct correlation between someone's economic system and their military expenditures.

And this isn't to say that more socialist = more peaceful militaries. It gets way more complicated than that in this world we live in. Though I would make the argument that if more powerful countries like USA, UK, and even China were more socialist and also no longer interested in advancing their hegemonies to keep and increase the profits of the few (again, dictionary definition of capitalism), then the world will be much better off.

Well yes, because it's true. That's why I cited a source. The countries doing things the "right way" with capitalism and the ones doing it the "wrong way" are both failing at meeting their own goals to stop runaway climate change.Exactly: That puts he US being as the main culprit of climate change, and still, you diminish every other (capitalist!) country contribution to do better as "not enough" and "there isn't a participation trophy for that".

I would also point out that the "right way" here involves gleefully collaborating with and relying on anyone doing things the wrong way as long as they're not batshit insane like Trump is. I'm not just talking about the US either, it's not like successful European nations are all that concerned with the state of social democracy in China.

I'm not accustomed to Marxist theories of alienation of labor but I'll try to give it a shot. In Marx's day, people were still primarily concerned with commodity production, so his examples involved 3 "productive"professions and 1 "unproductive" profession. With the industrialization of agriculture we have collapsed all the food production professions to 'indistrialized farmer", and hunting and fishing are now primarily hobbies in modern society.[/QUOTE]Good stuff all around, but I'm interested in your thoughts about this Marx statement:

What, then, constitutes the alienation of labor?First, the fact that labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind.The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home. His labor is therefore not voluntary, but coerced; it is forced labor....For as soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape.He is a hunter, a fisherman, a herdsman, or a critical critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Can this view work for an updated society? Rhetorical question because it definitely can and does, but the examples Marx uses aren't relevant for a lot of people these days, so some might balk at it. Is there a nice easy way to update the examples here or come up with some other scenarios that can help 21st century folks living in a service based society like ours?

I think if you were updating that for today, you'd need to change the ratio of production vs nonproduction. Instead of hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic, perhaps farmer, chef, coder, shitposter? For a 1:2:1 ratio of commodity:service:entertainment, whereas he had a 3:1 ratio of commodity:entertainment.

My protocol for these kinds of topics is mainly to try to introduce people to ideas of worker ownership, which is pretty simple and intuitive for people raised and educated under capitalism. The end of professional specialization (which is what I assume Marxist alienation is concerned about) that would be brought about by communism is probably too whimsical for the level of discourse we're engaging in. It'd be like trying to explain calculus to people who have not even grasped algebra.Because this aspect of socialism is often the one seen as a pipe dream, and why we typically hear all these "human nature" arguments as to why it's a waste of time to even talk about. Cause apparently human nature means resigning ourselves to a system built by and catered to as few as possible. It's human nature to expect less for more work done, and where most of the profits of that work don't go into yourself or the community but to a few individuals owners.

From my understanding of Marx, he believed that labor could only be fulfilling if you chose to do it (i.e. cooking a birthday dinner for your spouse) instead of being obligated to do it by everyday economics (i.e. catering a birthday dinner for someone else). So, both the caterer and the spouse do the same amount of work (birthday dinner) but the former is not alienated from their labor while the latter is (though not always). Some people find fulfillment merely in cooking for others and in those rare circumstances where a wage laborer finds themselves fulfilled by their profession they are usually much happier than and the envy of their peers. Hundreds of pages of literature has been written on trying to find fulfillment in your profession, or finding a professional "track" that is fulfilling, so it is clearly a very desirable thing, though the perversity of modern capitalism is trying to convince you that there's something wrong with you if you don't love to work for your boss, and we have created a generation of "workaholics" who have, whether genuinely or not, convinced themselves they love wage labor.

I have drifted away from the original point so I'll call it here. I guess the clearest way I could put it is "socialism wants to make sure you get the most out of your work, financial and emotional, instead of giving up a fraction of it to your boss out of necessity of survival".

You one of those types that thinks militaries are there to "protect freedoms" and such? They ensure the capital of the state. They're enforcers.

And that's why there shouldn't be any form of military forces anywhere. They serve no purpose in a modern civil world.

It's worth noting that the "pop culture figures" in socialism/communism looooove to wear military uniforms, even though they are meant to represent the "kind spirit" of the movement they lead/led.

Last edited:

Yea I meant more his take on it with the his add-on of surplus value. I think that's what it was called and that it was his idea?Can you provide a definition, in your own words, of the LTV? It's not that I don't know of it but Marx did not actually put forth a LTV. He drew from Ricardo and Smith here though of course he contributed his own ideas about value.

I haven't red Marx or any critique of him in a bit so this is just what I can remember/top of my head. So I might be wrong/misunderstanding something. My formal education is more on the investment, business, accounting side so I'm not an economist or expert in this area.

So basically labour theory of value (LTV) is that labour is the only source of added value. What Marx did was add the socially necessary part to labour, that is that the labour had to do something valuable. I think that the also added that this labour value added was based an averages, so that someone who is low skilled in a task has less labour time value (?) than someone more skilled.

Then you have the surplus value, which is the sales price minus the cost of inputs to produce the commodity; i.e. the profit. This is the part that he said capitalists are exploiting. As he said capitalists aren't doing any labour, and that is the only source of added value. So for them to get value they need to exploit the surplus value of others labour.

He also said something about prices gravitating about some point based on acclimated labour value I think. Something equivalent to equilibrium prices.

So now from what I gather LTV has been discarded and replaced with marginal theory in modern economics. This is as there where some flaws with LTV.

A big one is that labour isn't the only source of value, or that value isn't something that can overall be quantifiable. It's something that varies between individuals and is based on comparisons to there things. The true cost of something isn't it's end price, but what you have to give up to get it, which is a vary individual thing.

Some basic examples as to why labour isn't the only source of value:

Wine - You create a barrel of wine, as soon as you've done so bottle some and sell it as fresh wine. Then let the wine age for a bit and sell another bottle some time later. The later bottle would have a higher value than the fresh despite having virtually identical amount of labour time. The extra value comes from time, you put off making profit now to make more later.

Crops - You have two crops, A and B, that both require the same input of labour per same yield. Capital input is the same except for land, A requires 50% more land that B for the same output yield. As land is both scarce (and isn't require any labour input as it's already there), A will have more value than B.

Marginal theory also gets rid of the exploitation of surplus value. The wage an employee makes is deemed worth more than their labor time, and the wage paid by the employer is with less than the labour they get in return. Both benefit from this trade or it wouldn't have taken place; no one is inherently exploited.

Yes in the real world this isn't a perfect free market in the Econ 101 sense but there are ways of combating this without getting rid of capitalism. An example would be a strong safety nets or a UBI so that if the worker takes on the job or not doesn't have an impact on their survival. So it comes back to margin theory, is the wage worth giving up their time that could be used for other things.

TL;DR: Marxs critique is that capitals is exploitative due to surplus value in with his LTV theory. LTV theory doesn't fit the evidence we have. So without it his critique of capitalism is flawed and therefore isn't inherently exploitative.

Last edited:

I'm not accustomed to Marxist theories of alienation of labor but I'll try to give it a shot. In Marx's day, people were still primarily concerned with commodity production, so his examples involved 3 "productive"professions and 1 "unproductive" profession. With the industrialization of agriculture we have collapsed all the food production professions to 'indistrialized farmer", and hunting and fishing are now primarily hobbies in modern society.

I think if you were updating that for today, you'd need to change the ratio of production vs nonproduction. Instead of hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic, perhaps farmer, chef, coder, shitposter? For a 1:2:1 ratio of commodity:service:entertainment, whereas he had a 3:1 ratio of commodity:entertainment.

Oh yeah, I'm a new one myself so was just wondering how others might approach this concept of the worker. And definitely agree with a more distributed ratio there.

And that's why there shouldn't be any form of military forces anywhere. They serve no purpose in a modern civil world.

It's worth noting that the "pop culture figures" in socialism/communism looooove to wear military uniforms, even though they are meant to represent the "kind spirit" of the movement they lead/led.

So I definitely agree with abandoning military forces. The dream would be to redistribute all of the resources to bread instead of guns, and give out more hope than paranoia. Climate change around the globe makes this even more urgent, and every military on earth should be transitioning away from war and conflict and more into relief and recovery efforts the planet over.

As for pop culture socialist icons and governments, I think that's a conversation about the power of struggle. You have an existential global superthreat in the USA, and then these smaller and poorer countries that are the underdogs. Most are literally just leaving their colonial and capitalist periods of subjugation and oppression.

And even if they win their self-determination, they will suffer the wrath of the 10+ corporations that own the USA for decades to come. So the issue of conflict and struggle is highlighted and used as a rallying point.

Liberalism didn't work until it did, they (feudal serfs) didn't say "liberalism never works which is why we need to stay in feudalism", (well maybe the conservative ones did) they just said "we think liberalism is pretty cool so we're going to overthrow the monarchy now". Which is how it works, you develop a theoretical justification for a thing, then you do the thing. You don't look at the past for successful examples of the future, this is literally not how either socialism or capitalism works!

I shouldn't be shocked anymore about Era member's grasp on history (and particularly American's conception of feudalism and the Middle Ages), but... holy shit.

Don't mind me, I'll be over there eating popcorn and waiting for someone to start talking about dragons and witches.

Is that so? Google the definitions of "democracy" and then "capitalism" to see what comes up.

???

democracy

/dɪˈmɒkrəsi/

Learn to pronounce

noun

- a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

/ˈkapɪt(ə)lɪz(ə)m/

Learn to pronounce

noun

- an economic and political system in which a country's trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state.

Okay, so what's commonly known as the labor theory of value (which wasn't critical to Marx's critique) is not the same thing as his theory of surplus value (which was critical to his critique) or his idea of socially necessary labor time, which you brought up. I was a bit confused there but now I know you want to talk about surplus value.So basically labour theory of value (LTV) is that labour is the only source of added value. What Marx did was add the socially necessary part to labour, that is that the labour had to do something valuable. I think that the also added that this labour value added was based an averages, so that someone who is low skilled in a task has less labour time value (?) than someone more skilled.

Yes that's correct.Then you have the surplus value, which is the sales price minus the cost of inputs to produce the commodity; i.e. the profit. This is the part that he said capitalists are exploiting. As he said capitalists aren't doing any labour, and that is the only source of added value. So for them to get value they need to exploit the surplus value of others labour.

Yeah, economics was not as advanced back then but this is analogous to the modern idea of equilibrium.He also said something about prices gravitating about some point based on acclimated labour value I think. Something equivalent to equilibrium prices.

It is true Marxian economics is less popular now, but that is not really due to fundamental flaws with the theory, but because Austrian economics (Mises, Hayek, etc), the people who made Marginalism, were better at making money and capitalists prefer systems that make money and they promoted ideas that made them money. Marxist theory is primarily concerned with worker/human welfare instead of profit. The progression of dominant economic paradigms is like, Ricardo/Smith -> Marx -> Hayek/Mises -> Keynes -> Friedman.So now from what I gather LTV has been discarded and replaced with marginal theory in modern economics. This is as there where some flaws with LTV.

You're talking about opportunity cost.A big one is that labour isn't the only source of value, or that value isn't something that can overall be quantifiable. It's something that varies between individuals and is based on comparisons to there things. The true cost of something isn't it's end price, but what you have to give up to get it, which is a vary individual thing.

The appreciating value of the bottle of wine still comes from the labor needed to grow the vines, press the grapes and store the juice. Just because value changes over time does not imply time creates value (although I would agree that it does, just not in the way you think), it is still coming from labor. No initial outlay of labor, no wine. Lastly, you make the same mistake as most modern laypeople (imo) which is that you think price is the same thing as value. A simple counterexample using wine. A half bottle from a famous vintage is poured out and refilled with a cheaper wine. This fake bottle is sold next to a real bottle. Both bottles have nominally the same price, but one is considered a scam and the other isn't. Their prices are the same but their "value" is different.Wine - You create a barrel of wine, as soon as you've done so bottle some and sell it as fresh wine. Then let the wine age for a bit and sell another bottle some time later. The later bottle would have a higher value than the fresh despite having virtually identical amount of labour time. The extra value comes from time, you put off making profit now to make more later.

The land use efficiency of a crop is analogous to the efficiency of a machine. Marx obviously accepted some machines are more efficient than others. His term for the value inherent in assets (land, machines, materials, etc) is "constant capital", as opposed to "variable capital", the money that is spent on wages. He would agree with you that B is worth more than A and it has no bearing on his theory of surplus value because seeds are a of type capital.Crops - You have two crops, A and B, that both require the same input of labour per same yield. Capital input is the same except for land, A requires 50% more land that B for the same output yield. As land is both scarce (and isn't require any labour input as it's already there), A will have more value than B.

Your mutually beneficial trade misses that the wage worker cannot acquire food without selling their labor as all land and sources of food have been monopolized by capitalists, and that their participation in this trade is contingent on the threat of starvation and/or homelessness. I doubt you could argue that forcing someone to work with the threat of starvation is a mutually beneficial trade. If we lived in a world where housing was free and food was free and you did not have to do any job you did not choose to, I'd feel differently about Marginalism, but we do not live in that world. We live in a world where you're compelled to enter the labor market by the threat of death. That is where the exploitation, in a Marxist sense, comes from, the compulsion brought about by monopoly (ownership) over the necessities of survival (food, water, shelter).Marginal theory also gets rid of the exploitation of surplus value. The wage an employee makes is deemed worth more than their labor time, and the wage paid by the employer is with less than the labour they get in return. Both benefit from this trade or it wouldn't have taken place; no one is inherently exploited.

That is, the employer is free to make the trade or not make the trade.

And the employee's choice is between taking the trade or dying on the streets.

That being said, obviously the employer is under some pressure (i.e. market forces) to make the trade more attractive to prospective employees in order to staff their business and compete with their rivals, I'm not denying this. However, their trade is nowhere close to the mortal threat that hangs like the Sword of Damocles over the employee's head.

One of the reasons marginalism is popular among capitalists is because it handwaves away tricky moral problems like "should we feed and shelter the homeless?" by justifying a "no" answer because doing so does not create profit in a "win-win" trade like the one you sketched.

Enlighten me where I went wrong. No I'm serious, I tried to condense about 300 years of liberal history to 100 words, I'm bound to leave out details, but I can't learn if you don't engage, but it's fine if you don't want to I'll just be here playing with my dragons and witches.I shouldn't be shocked anymore about Era member's grasp on history (and particularly American's conception of feudalism and the Middle Ages), but... holy shit.

I fully admit I'm not as well read on history as I'd like so consider this a formal invitation to school me.

Last edited:

Didn't mean to confuse. Like I said it's been a bit since I've looked at the specifics. And I was/am still under the impression that LTV was still critical of his critique? If it's not required and you don't use marginalism to determine value then what?Okay, so what's commonly known as the labor theory of value (which wasn't critical to Marx's critique) is not the same thing as his theory of surplus value (which was critical to his critique) or his idea of socially necessary labor time, which you brought up. I was a bit confused there but now I know you want to talk about surplus value.

Isn't this and other arguments against economists a bit conspiratorial? That is they are only for it because it makes them money. This is similar to the arguments used against climate scientists, they're only doing it for the big research $$$.It is true Marxian economics is less popular now, but that is not really due to fundamental flaws with the theory, but because Austrian economics (Mises, Hayek, etc), the people who made Marginalism, were better at making money and capitalists prefer systems that make money and they promoted ideas that made them money.

The appreciating value of the bottle of wine still comes from the labor needed to grow the vines, press the grapes and store the juice. Just because value changes over time does not imply time creates value (although I would agree that it does, just not in the way you think), it is still coming from labor. No initial outlay of labor, no wine. Lastly, you make the same mistake as most modern laypeople (imo) which is that you think price is the same thing as value. A simple counterexample using wine. A half bottle from a famous vintage is poured out and refilled with a cheaper wine. This fake bottle is sold next to a real bottle. Both bottles have nominally the same price, but one is considered a scam and the other isn't. Their prices are the same but their "value" is different.

In my example though both bottles would have had the same labour inputs. The fresh bottle still needs labour to grow the vines, press and store the juice as the aged. So both need the same outlay of labour but have different values. And I'd be interested in you view on time to value, my understanding mainly comes from an accounting pov.

As for your wine example that difference in value would be because there is a imbalance in information between the seller and buyer; it's a market failure. And with price-value, value is what something is worth to someone and can be measured in the cost they are willing to part for it. So while the price and value aren't the same they can be compared.

This could be a flaw in my understanding of his critique (requirements of LTV) as I was more coming at it from a marginal value perspective.The land use efficiency of a crop is analogous to the efficiency of a machine. Marx obviously accepted some machines are more efficient than others. His term for the value inherent in assets (land, machines, materials, etc) is "constant capital", as opposed to "variable capital", the money that is spent on wages. He would agree with you that B is worth more than A and it has no bearing on his theory of surplus value because seeds are a of type capital.

Like I said though with a proper safety net this wouldn't be the case. Yea the market for labour isn't currently perfectly free and competitive but imo it's not a flaw with capitalism that is insurmountable. Unemployment benefits already aren't unheard of. This is why I'm a big fan of a UBI, it's something that really needs t be looked into.Your mutually beneficial trade misses that the wage worker cannot acquire food without selling their labor as all land and sources of food have been monopolized by capitalists, and that their participation in this trade is contingent on the threat of starvation and/or homelessness. I doubt you could argue that forcing someone to work with the threat of starvation is a mutually beneficial trade. If we lived in a world where housing was free and food was free and you did not have to do any job you did not choose to, I'd feel differently about Marginalism, but we do not live in that world. We live in a world where you're compelled to enter the labor market by the threat of death. That is where the exploitation, in a Marxist sense, comes from, the compulsion brought about by monopoly (ownership) over the necessities of survival (food, water, shelter).

That is, the employer is free to make the trade or not make the trade.

And the employee's choice is between taking the trade or dying on the streets.

I don't think it really hand wave away. Just giving homeless food/selter might not be economically efficient (imo it probably is due to the increased economic activity they would be able to then do), but it's not equitable. It's the difference between a positive and normative statement.One of the reasons marginalism is popular among capitalists is because it handwaves away tricky moral problems like "should we feed and shelter the homeless?" by justifying a "no" answer because doing so does not create profit in a "win-win" trade like the one you sketched.

I had a look at this and it's way beyond my economic understanding. Though what I can gather it hasn't actually been 100% settled, and that it's more of a theoretical issue not something that big of a deal irl.mentok15 : The Cambridge capital controversy showed that the basic marginal concept of capital doesn't work, and that production functions where income is equated to contribution to production are tautological.

Last edited:

No you're right, he built off the Ricardian/Smithian theory of value (which was based on labor) because marginalism didn't exist back then, and added the "innovation" of socially necessary labor time.Didn't mean to confuse. Like I said it's been a bit since I've looked at the specifics. And I was/am still under the impression that LTV was still critical of his critique? If it's not required and you don't use marginalism to determine value then what?

Not really? Advertising and marketing works the same way. Companies want to sell a commodity so they create media extolling the virtues of that commodity. Politics are subject to the same market forces, as well as economic theories. Businesses like deregulation and tax breaks, so they support politicians who promise deregulation and tax breaks. Businesses like economic models that don't care about worker welfare, so they promote those models in public discourse and through lobbying. They even have social clubs for it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mont_Pelerin_SocietyIsn't this and other arguments against economists a bit conspiratorial? That is they are only for it because it makes them money. This is similar to the arguments used against climate scientists, they're only doing it for the big research $$$.

Yeah, I was suspecting this was where you were going but I did not want to assume. Reading this, I think you seem to think that the LTV says that if the equivalent amount of labor was done then the resultant products should be worth the same. This is not the LTV, or any version of it I'm familiar with.In my example though both bottles would have had the same labour inputs. The fresh bottle still needs labour to grow the vines, press and store the juice as the aged. So both need the same outlay of labour but have different values. And I'd be interested in you view on time to value, my understanding mainly comes from an accounting pov.

If you grow grapes in Napa Valley and you grow grapes in Champagne, Marx would agree that you would have two different products with different values, despite comparable labor spent. His point was that there is no wine if there is no labor outlay, not that growing grapes in Napa Valley produces the same thing as growing grapes in Champagne.

Every child knows that a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a week, would perish.

-Marx

I'm not exactly certain, but you seem to think the LTV says the labor inputs should determine the price/value of the outputs and not supply/demand so that if two crops require the same amount of labor but have different yields, that Marxist economics says they should have the same price, did I interpret you correctly? Well, suffice to say, this is not what Marx or Marxists believe.This could be a flaw in my understanding of his critique (requirements of LTV) as I was more coming at it from a marginal value perspective.

I'll pull from wiki here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labor_theory_of_value#Karl_Marx

Contrary to popular belief Marx never used the term "Labor theory of value" in any of his works but used the term Law of value,[47] Marx opposed "ascribing a supernatural creative power to labor", arguing as such:

Here, Marx was distinguishing between exchange value (the subject of the LTV) and use value. Marx used the concept of "socially necessary labor time" to introduce a social perspective distinct from his predecessors and neoclassical economics. Whereas most economists start with the individual's perspective, Marx started with the perspective of society as a whole.Labor is not the source of all wealth. Nature is just as much a source of use values (and it is surely of such that material wealth consists!) as labor, which is itself only the manifestation of a force of nature, human labor power.[48]

I'm not sure where you learned the LTV but whatever you learned is a bit of a straw man. Marx understood and agreed with supply/demand. In your crops example, your seeds are a type of capital and some types of capital (raw material) are more productive than others (e.g., pure iron ingots vs impure iron ingots).

After thinking about it some more, I think I understand where your argument about the wine is coming from now. Let me know if I have it right. I'm going to use price = value here for simplicity's sake but it is not what I believe. I believe that price is an estimate of value and that real value is not quantitatively measurable, the best we can do is estimate it with imperfect discrete systems like price or GDP.

So, a bottle of red wine sells for $12. It is produced at t0. The producer is a wage worker who gets paid by the bottle and gets $10 per bottle, and the vineyard owner now has a $12 bottle after a $10 outlay. However, instead of selling the bottle, the owner stores it away, where it appreciates. It is now t1 and the bottle is worth $312, for $300 in appreciation. So you seem to think that the increase in value comes from the opportunity cost the owner "spent" in not realizing the value of the bottle before t1. That the value comes from the owner's "self control", and since the worker did not contribute their labor to the "self control", that the asset appreciation was not exploitative in the Marxist sense.

My rebuttal to this would be that the exploitation happened when the owner paid $10 for the production of a variable value asset that was worth at least $12 but could be worth $300 or more. That just because the bottle was worth $12 at t0 doesn't mean the owner only extracted $2 from the worker, the owner extracted the t0 surplus and all potential surplus contained within the bottle. If that sounds crazy it is because my ideas about value are pretty unorthodox. From a philosophical viewpoint, the bottle didn't become more valuable ex nihilo, what gave it value was the conditions of society that would create a market for a $312 vintage and those social conditions were created by people and thus human labor power. If there were no people, it would not matter how old the wine bottle is. The main insight of Marx and Marxism for me, and I'm going to separate "price" from "value" here again, is that value comes from the relationships between people and price is a crude estimate of this value. In mainstream economics, price is king, but in my own understanding of Marxist economics, price is just an imperfect measure of value, which is the real underlying mover of economics.

(Also, the storage and maintenance of the wine bottle still took labor. A wine bottle, as an appreciating asset, is a lot like like land. Sometimes land is not worth a lot until conditions change like "an oil deposit was discovered" or "we need space for a wind farm". The value of assets changing over time does not disprove LTV.)

Taking this from another angle, with the COVID crisis we have since separated workers into "essential" (the work society cannot function without) and "non-essential" (the work society can function without). Marginalism is not able to distinguish between essential and non-essential work in normal times and it took the force of the pandemic to create such a distinction, but Marxists were already aware of the existence of "non-essential" work, even before COVID. Leftist ideas about landlords or middle managers or bullshit jobs have already labeled a vast swathe of the pre-pandemic economy as "non-essential". This is one of the strengths of Marxist economic theory over mainstream "neoclassical" theory. Marxism is grounded in the physical conditions of the world rather than idealized mathematical models that don't account for human need. The idea that any work that gets a price in the market is justified is one consequence of marginalism; Marxism says "no, only what's deemed necessary by society has value". For a lot of us socialists, the macroeconomic fallout of the pandmic (e.g. essential workers, stimulus payments, etc.) are a vindication of Marxist ideas about economics.

Debate persists about the implications and appropriate responses, but it's certainly settled as to which side of the debate(s) was correct. It's a theoretical issue in that it's an issue with the theory, just like the transformation problem is for some Marxian analysis. The extent to which it's a big deal IRL depends on the ways in which these theories are used by people to inform and shape social structures.I had a look at this and it's way beyond my economic understanding. Though what I can gather it hasn't actually been 100% settled, and that it's more of a theoretical issue not something that big of a deal irl.

My counter-argument would be that even that level of dissent would be enough to upend a mutually cooperative social system, at least at the scales we're talking about. One of the annoying ironies of collectivism is that it becomes much harder to deal with dissention the larger the social structure becomes, and it's obvious why when you think about it. A group of 10 people kicking out 1 person for being an asshole is easy. A group of a million people fighting a civil war against 100,000 is an international crisis. Sure, having superior numbers means you'll probably win such a conflict eventually, but on an absolute level you would be asking a chunk of your one million fellow workers, a significant amount of people I might add, to potentially sacrifice themselves in the name of their social order. Sure, if the group's conviction and belief in their system is strong enough then the people might be willing, but even the mere threat of that level of enforcement being necessary weakens the social structure on its own. A centralized ruling class can deal with this better than a collectivist one can, not because it's inherently "better" or anything like that, but just because of logistics. An unruly rebellion can be placated by overthrowing the current ruling class and replacing them with a new one. What the heck do you do when there is no ruling class. By that point, you're better off just kicking them out or killing them off. Or, perhaps even easier, just kind of letting them be there in perpetual stalemate.

If that level of dissent was honestly enough, we'd all already be living in a social democracy at the very least or a socialist society at best. There's far more aspects and pieces to this that you aren't placed on the table, clearly, or are assuming that such a world would not have some sort of safeguard against dissent.

To the bolded line in your response here, people already did and do join up to serve and die in conflicts with FAR more abstract goals in far greater numbers. But "preserving your exit from wage slavery and/or poverty for you and your loved ones" seems like a pretty non-abstract goal people would be willing to protect for pretty obvious reasons.

But as you rightfully point out later, the idea that armed conflict would happen after the establishment of socialism is on the side of unlikely, when it's at least somewhat more likely to happen before with people fighting to end the ills of capitalism.

Now that's kind of an extreme example, and I'm not saying dissention will automatically escalate to armed conflict, but the point is that 3% of a whole lot of people is still a whole lot of people, and when a whole lot of people are involved it's never as simple as "we have more people than you therefore we win". Unless we're talking about an election but then if democracy could solve this theoretical problem, it already would have.

There's a lot of reasons democracy can't solve the problem in and of itself that are so obvious that they don't require re-stating.

But as most visible minorities, invisible minorities and openly-oppressed groups will tell you, yeah, nearly all of human history is "we have more people than you, therefore we win". The only reason minority populations and/or the oppressed have any rights at all is that a majority eventually appeared that considered certain conditions for those minorities and oppressed groups to be unfair and/or inhumane, but that core principle of majority rule has existed since liberalism replaced feudalism/monarchism as the dominant set of societal principles of the Western world. The only thing one can do is shape the opinions of what the majority wants.

Who said here that socialists were gonna take your house? You're wasting a huge amount of everyone's time by shadowboxing an argument that no one made. It's exhausting and I'd beg you to stop doing it, but I don't want to get my knees dirty for something I'm unsure you'd grant the courtesy of anyways.No but it sounds like some of you might want to take my house, and you can't fucking have it.

And besides, if we're going to talk about land being stolen... living in Texas specifically but North America more generally doesn't provide much of a leg to stand on. "You can't steal my land that someone 'graciously' stole from Mexico and the Indigenous peoples of the region on my behalf, how DARE you" isn't a position of strength for such an argument, though I'm sure that original land theft is easily put out of mind on a regular basis because of how inconvenient it is to think about when crowing about your right to property.

Property ownership is, when you recall how that land came into possession in the first place as history clearly illustrates, a very tenuous concept at the best of times, to say nothing about all the ways capitalism can take it from you as it is, like how current federal and state law enforcement can take it from you on a whim using trumped-up accusations of criminal wrongdoing and place all the onus on you to get it back (civil forfeiture sure is total shit, huh?).

But lastly, since you brought it up, we rightfully criticize corporations for profiteering from basic human needs and rights (see: Nestle and their stance on water reserves). Adequate housing is also a fundamental human right, so I see profiteering off of that as you seem to aspire to do as distasteful for similar reasons. To hold one human right as sacrosanct and another as open for rampant profiteering would be hypocrisy, in my mind.

First of all, my main point in that previous post is that Capitalism isn't perfect, but clearly other countries handle it better (miles better) than the US, which is the main source of complains in this thread: Let's talk about healthcare in Canada or France, or even the UK, let's talk about food warning labels in Chile, let's talk about livable city design in Europe... and most of those countries have capitalist systems with medium/strong left-wing political parties in charge.

As long a ruling Socialist party (in any country) aims towards improving Capitalism, there isn't much to complain about... But if it goes "capitalism is the root of all problems" then is just populism disguised as a political view.

As a Canadian, gonna raise my hand and say that just because I and my fellow Canadians are not going to bankrupt ourselves on medical expenses doesn't mean that it's somehow doing a great job to alleviate all the other ills of capitalism that are still immediately present. Honestly, our socialized healthcare was practically a fluke as it is and hardly an example; in spite of the good it does for the people, there's been little to no expansion of socialized healthcare since it was established in the 60s, despite the success it's been. No pharmacare, no coverage for dentistry or optometry, no coverage for mental health except for emergency psychotherapy... for something so successful at the goals it set out to achieve, you would naturally think expansion would be the outcome, but it's not.

It sounds more achievable because social democracy is loaded with patchwork and compromise to make it appear as such (and "how on earth could compromise NOT make something more achievable?" is the prevailing thought pattern there), but I've argued for a long time that the same kind of will from the public and political/revolutionary effort is required to achieve either socialism or social democracy sustainably, so the only reason to argue for one over the other is to retain capitalism.To me, Social Democracy is the closest to a achieveable and succesful socialist system implementation I can see.

Taking that into account, then yes, socialism (social democracy) can be implemented, and not only as a goal far away into the future, but actually anywhere at any time.

It's also important to remember that FDR's New Deal was social democratic in nature, and... yeah, that's pretty well fully eroded away thanks to the likes of Goldwater and all those he was supported by and those he propped up (like Reagan and the new breed of politician that era created). So social democracy's potential success is fleeting at best or highly precarious at worst.

Social democracy, because it maintains capitalism and thus retains capitalists who always seek to undo social safety nets, is like trying to leash a starving wolf while constantly touring a chicken coop. Would seem more sensible to not allow the wolf inside at all.

TIL the American, Glorious and French Revolutions happened in the Middle Ages.I shouldn't be shocked anymore about Era member's grasp on history (and particularly American's conception of feudalism and the Middle Ages), but... holy shit.

Don't mind me, I'll be over there eating popcorn and waiting for someone to start talking about dragons and witches.

Probably in your best interests not to lecture people on their grasp of history when liberalism as a political philosophy wasn't even really a proper thing until around the Age of Enlightment. But hey, at least you got a pointless zinger in, right? Always good to have one's priorities straight.

Oh, BTW, while you eat your popcorn, your ab absurdo fallacy is showing, might want to take care of that.

TIL the American, Glorious and French Revolutions happened in the Middle Ages.

Probably in your best interests not to lecture people on their grasp of history when liberalism as a political philosophy wasn't even really a proper thing until around the Age of Enlightment. But hey, at least you got a pointless zinger in, right? Always good to have one's priorities straight.

I think the poster is mocking the common idea that feudalism was followed by liberalism and not in fact the age of absolute monarchies(feudalism ended in the 15th century) which is indeed common for a lot of people not from Europe to make even though the two are actually not that comparable if one looks beyond the surface level reality of kings being the face of nations. I guess the fact that both ways of governance are hereditary is the most confusing part for a lot of people, which imo is a justifiable mistake to make if one hasnt looked deep into it, being fair to Samoyed.

Last edited:

Honestly I am unsure where my idea of LTV actually came from. Had a little look and found this from Ricardo:Yeah, I was suspecting this was where you were going but I did not want to assume. Reading this, I think you seem to think that the LTV says that if the equivalent amount of labor was done then the resultant products should be worth the same. This is not the LTV, or any version of it I'm familiar with.

Which seems to say what I'm thinking, I think?The value of a commodity, or the quantity of any other commodity for which it will exchange, depends on the relative quantity of labour which is necessary for its production, and not on the greater or less compensation which is paid for that labour.

It also seems to be from Ricardo where I got the wine analogy:

I cannot get over the difficulty of the wine, which is kept in the cellar for three or four years, or that of the oak tree, which perhaps originally had not 2 s. expended on it in the way of labour, and yet comes to be worth £100.

Yes that's what I meant. So I do agree with Marx, at least on some things.I'm not exactly certain, but you seem to think the LTV says the labor inputs should determine the price/value of the outputs and not supply/demand so that if two crops require the same amount of labor but have different yields, that Marxist economics says they should have the same price, did I interpret you correctly? Well, suffice to say, this is not what Marx or Marxists believe.

I'll pull from wiki here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labor_theory_of_value#Karl_Marx

I'm not sure where you learned the LTV but whatever you learned is a bit of a straw man. Marx understood and agreed with supply/demand. In your crops example, your seeds are a type of capital and some types of capital (raw material) are more productive than others (e.g., pure iron ingots vs impure iron ingots).

Yep that is pretty much what I was thinking. But then I would add that the increased value over time isn't guaranteed, things can change in that time.After thinking about it some more, I think I understand where your argument about the wine is coming from now. Let me know if I have it right. I'm going to use price = value here for simplicity's sake but it is not what I believe. I believe that price is an estimate of value and that real value is not quantitatively measurable, the best we can do is estimate it with imperfect discrete systems like price or GDP.

So, a bottle of red wine sells for $12. It is produced at t0. The producer is a wage worker who gets paid by the bottle and gets $10 per bottle, and the vineyard owner now has a $12 bottle after a $10 outlay. However, instead of selling the bottle, the owner stores it away, where it appreciates. It is now t1 and the bottle is worth $312, for $300 in appreciation. So you seem to think that the increase in value comes from the opportunity cost the owner "spent" in not realizing the value of the bottle before t1. That the value comes from the owner's "self control", and since the worker did not contribute their labor to the "self control", that the asset appreciation was not exploitative in the Marxist sense.

Here I'm a little confused. In what way would do you view the condition of society allowing for this market? It seems a little in the subjective value theory (which I more agree with), but then really not.My rebuttal to this would be that the exploitation happened when the owner paid $10 for the production of a variable value asset that was worth at least $12 but could be worth $300 or more. That just because the bottle was worth $12 at t0 doesn't mean the owner only extracted $2 from the worker, the owner extracted the t0 surplus and all potential surplus contained within the bottle. If that sounds crazy it is because my ideas about value are pretty unorthodox. From a philosophical viewpoint, the bottle didn't become more valuable ex nihilo, what gave it value was the conditions of society that would create a market for a $312 vintage and those social conditions were created by people and thus human labor power. If there were no people, it would not matter how old the wine bottle is. The main insight of Marx and Marxism for me, and I'm going to separate "price" from "value" here again, is that value comes from the relationships between people and price is a crude estimate of this value. In mainstream economics, price is king, but in my own understanding of Marxist economics, price is just an imperfect measure of value, which is the real underlying mover of economics.

My view of the pandemic is that some societies produce cooperators and some societies produce selfishness and US society is one of the latter, mostly due to its dominant ideology (laissez faire capitalism).

It's basically collectivism (the east) vs individualism (the west)

Hence why China's been back to normal since october and there's live music concerts and shit

The Age of Absolutism (or whatever you wish to call it) and the time of mercantilism that arose from it (which some simply refer to as proto-capitalism, but that's a whole other discussion) is frankly a tiny blip in between feudalism and the proliferation of liberalism/capitalism proper.I think the poster is mocking the common idea that feudalism was followed by liberalism and not in fact the age of absolute monarchies(feudalism ended in the 15th century) which is indeed common for a lot of people not from Europe to make even though the two are actually not that comparable if one looks beyond the surface level reality of kings being the face of nations. I guess the fact that both ways of governance are hereditary is the most confusing part for a lot of people, which imo is a justifiable mistake to make if one hasnt looked deep into it, being fair to Samoyed.

But this period still held several key traits of feudalism in several parts of Europe right up until the 1800s, if not the precise definition of it. There is no clear line drawn between where one system began and another ended, nor does it really matter for much of the general population whose material conditions didn't change as much as people think they did until the fall or neutering of monarchies (and in turn the few lords who sustained power) through the transition to liberalism.

I think a lot of people get this backwards, most people would probably be for socialism, if they understood what it was, and had to option to experience it without oppression, and without the powerfully focal opposition. The majority of people aren't selfish, they just want to peacefully get on with their life. The problem is that the handful of extreme anti-socialists are so loud, and aggressive in their beliefs, that they silence the majority. Not to mention that there are only tiny minority of actual Capitalists, and they have all to control, so can easily suppress any attempts to move away from their prefered sytem by controlling the narrative, or even using actual force.

The Age of Absolutism (or whatever you wish to call it) and the time of mercantilism that arose from it (which some simply refer to as proto-capitalism, but that's a whole other discussion) is frankly a tiny blip in between feudalism and the proliferation of liberalism/capitalism proper.

But this period still held several key traits of feudalism in several parts of Europe right up until the 1800s, if not the precise definition of it. There is no clear line drawn between where one system began and another ended, nor does it really matter for much of the general population whose material conditions didn't change as much as people think they did until the fall or neutering of monarchies (and in turn the few lords who sustained power) through the transition to liberalism.

I dont think the government systems really changed much of what the common people experienced, i feel that if there was no industrial revolution regardless of the philosphy of the time you wouldnt have seen much change, and if the age of absolutism is a "blip" then doesnt the same apply to capitalism? I mean a couple hundred years is still like 5 generations living through it.

I think its fair to correct people on it, knowing what feudalism is and how it failed and was supplanted by parliamentary and absolutist monarchies basically answers the question "why does Europe still have kings?" by itself at the very least.

Ricardo was the big economist of Marx's day (basically the 19th century's Keynes or Friedman), along with Smith. Marx built off of Ricardo and Smith because that's all he had but was not a dogmatic follower of them. The Ricardian LTV is closer to what you gave.Honestly I am unsure where my idea of LTV actually came from. Had a little look and found this from Ricardo:

Which seems to say what I'm thinking, I think?

It also seems to be from Ricardo where I got the wine analogy:

In Marxist economics, production is in a social context, but so is consumption. By "conditions of society" I meant there is a place to sell a $300 bottle of wine (maybe a restaurant) and a culture that ascribes value to old wines. The restaurant was constructed and maintained by human labor power. The culture of wine drinking is maintained by human labor power (wine critics, wine storage, wine shops, etc). So, the t1 bottle of wine needed not just the owner's "self control" but the existence of a social context that values old wines. I thought of another example to try to illustrate what I mean, hopefully this doesn't make things more confusing.Here I'm a little confused. In what way would do you view the condition of society allowing for this market? It seems a little in the subjective value theory (which I more agree with), but then really not.

Let's reuse the previous setup, that of the vineyard owner and worker and the $12 of wine. After bottling and storing the wine, war breaks out and both the owner and worker are killed by enemy soldiers. Now the bottle is "lost". After the war ends, let's say t1 again, the bottle is rediscovered by construction workers. The war did not disrupt the aging of the wine (I do not know how wine aging works I assume it's something like this) and the bottle is worth $312 again, plus maybe another $1000 for the prestige of being a "lost" wine from before the war.

So, where did the t1 value, $1312, come from, the worker, the owner, the construction worker or the enemy soldiers? As before I would say the $312 "EV" of the aged bottle came from the worker, even if it required the "self control" of the owner to not realize the value ahead of time, as we see from the war scenario, even if you remove self control from the equation the wine still appreciates. The wine is now appreciating capital like works of art and antiques. Furthermore, I would argue that the additional $1000 of prestige comes from the construction of a post-war society that values pre-war wines, and it is impossible to attribute this value to any one person in a neat and tidy way, it is the sum total of everything that happened between t0 and t1 (the war, the soldiers killing the owner and worker, the construction worker rediscovering it, the post-war society that still values pre-war wines, etc). That is, the value comes from the total history of society.

This is where Marxism gets into very deeply philosophical territory. If all value comes from shared human history, then why are there ultra-rich next to deep poverty? I admit trying to resolve this idea using modern accounting practices is impossible but you can see how this would naturally lead Marx to the conclusion of communism, i.e. "everyone shares everything in common", it is because he, and the Marxists that followed him, believe that everything has value only in so far as it fits somewhere into human history and that no single person owns history. In Marx's day, the idea that major figures moved history was known as the Great Man theory. However, Marx did not believe in this theory, he believed in the stochastic movement of the masses, i.e. historical materialism. So he could not really attribute the creation of historical social value to singular people. Marxism demands that you always look at the context of human relations (aka we live in a society).

I dislike the collectivism vs individualism dichotomy because I consider it a relic of Cold War propaganda but it does have some explanatory power here. I would not describe most Chinese as diehard collectivists, they are usually as self-interested as Westerners, which is why they took to consumerism so readily, but they have not lost trust in public institutions the way the West did. There is resentment of the elite the same way there is everywhere, but it does not go as far as "Jacky Ma is spreading COVID through 5G Huawei towers" which is how bad it's gotten in the West.It's basically collectivism (the east) vs individualism (the west)

I did not know there was a difference, categorically, between feudalism and absolute monarchism so that is mea culpa. I should mention that I use feudalism as a stand in for "age of kings and serfs".I think the poster is mocking the common idea that feudalism was followed by liberalism and not in fact the age of absolute monarchies(feudalism ended in the 15th century) which is indeed common for a lot of people not from Europe to make even though the two are actually not that comparable if one looks beyond the surface level reality of kings being the face of nations. I guess the fact that both ways of governance are hereditary is the most confusing part for a lot of people, which imo is a justifiable mistake to make if one hasnt looked deep into it, being fair to Samoyed.

Thanks for that write up, it's definitely something to think about.Ricardo was the big economist of Marx's day (basically the 19th century's Keynes or Friedman), along with Smith. Marx built off of Ricardo and Smith because that's all he had but was not a dogmatic follower of them. The Ricardian LTV is closer to what you gave.

In Marxist economics, production is in a social context, but so is consumption. By "conditions of society" I meant there is a place to sell a $300 bottle of wine (maybe a restaurant) and a culture that ascribes value to old wines. The restaurant was constructed and maintained by human labor power. The culture of wine drinking is maintained by human labor power (wine critics, wine storage, wine shops, etc). So, the t1 bottle of wine needed not just the owner's "self control" but the existence of a social context that values old wines. I thought of another example to try to illustrate what I mean, hopefully this doesn't make things more confusing.

Let's reuse the previous setup, that of the vineyard owner and worker and the $12 of wine. After bottling and storing the wine, war breaks out and both the owner and worker are killed by enemy soldiers. Now the bottle is "lost". After the war ends, let's say t1 again, the bottle is rediscovered by construction workers. The war did not disrupt the aging of the wine (I do not know how wine aging works I assume it's something like this) and the bottle is worth $312 again, plus maybe another $1000 for the prestige of being a "lost" wine from before the war.

So, where did the t1 value, $1312, come from, the worker, the owner, the construction worker or the enemy soldiers? As before I would say the $312 "EV" of the aged bottle came from the worker, even if it required the "self control" of the owner to not realize the value ahead of time, as we see from the war scenario, even if you remove self control from the equation the wine still appreciates. The wine is now appreciating capital like works of art and antiques. Furthermore, I would argue that the additional $1000 of prestige comes from the construction of a post-war society that values pre-war wines, and it is impossible to attribute this value to any one person in a neat and tidy way, it is the sum total of everything that happened between t0 and t1 (the war, the soldiers killing the owner and worker, the construction worker rediscovering it, the post-war society that still values pre-war wines, etc). That is, the value comes from the total history of society.

This is where Marxism gets into very deeply philosophical territory. If all value comes from shared human history, then why are there ultra-rich next to deep poverty? I admit trying to resolve this idea using modern accounting practices is impossible but you can see how this would naturally lead Marx to the conclusion of communism, i.e. "everyone shares everything in common", it is because he, and the Marxists that followed him, believe that everything has value only in so far as it fits somewhere into human history and that no single person owns history. In Marx's day, the idea that major figures moved history was known as the Great Man theory. However, Marx did not believe in this theory, he believed in the stochastic movement of the masses, i.e. historical materialism. So he could not really attribute the creation of historical social value to singular people. Marxism demands that you always look at the context of human relations (aka we live in a society).

Have you read anything on Henry George, he was a contempt of Marx? While not the same the social aspect you described reminds me on his views on land value and rents. I've only discovered him recently but I think some of his ideas are interesting, his Savannah Story for example.

The figurehead of the Georgists, I do not know much about him, but I have seen some of my positions described as Georgist by people who are much better at leftist history than I am. I will read the Savannah Story later, my readings are piling up again, thanks for the link.

His (very) basic idea is that land gets its value from societies economic activity that occurs around it; everyones labour. This value should then be shared by society at large, not the landlord who owns the land. This value landlord extract is rent, and should be taxed and then shared through a citizens dividend.The figurehead of the Georgists, I do not know much about him, but I have seen some of my positions described as Georgist by people who are much better at leftist history than I am. I will read the Savannah Story later, my readings are piling up again, thanks for the link.

Quick TL;DR for any one interested from the link

RENT AND EARNINGS

An important lesson that may be drawn from Henry George's Savannah Story is how the wealth that is produced within an economic community divides between (a) the rent which people who compete with each other for a location must pay and (b) the earnings (i.e. wages plus interest) which the suppliers of labour and capital receive for their endeavours and enterprise.

In a simple economy Rent is small compared with Earnings whilst in a highly developed community, where there is much specialisation and trade, Rent represents a large share of a much larger amount of total and average wealth produced. Average and total Earnings may be larger but compared with Rent they represent a smaller share.

From this it may be appreciated how Rent is produced by the presence, protections and services provided by the whole community and thus forms a natural source of public revenue in place of taxes on the wealth produced by individuals and groups.

Last edited:

I think the point is that feudalism really didn't have this clear end point where absolute monarchies and mercantilism completely supplanted it, first of all; they ran in parallel to each other for a great number of decades and lasted in France specifically via the Ancien Régime right up until the Revolution, so the implication that serfdom was somehow non-existent in the world leading up to the liberal revolutions is very much not a position supported by historic record. Judging and laughing at posters for their suggested lack of knowledge of history seems pretty misguided when considering the omissions of history one has to engage in to believe such a take is historically inaccurate.I dont think the government systems really changed much of what the common people experienced, i feel that if there was no industrial revolution regardless of the philosphy of the time you wouldnt have seen much change, and if the age of absolutism is a "blip" then doesnt the same apply to capitalism? I mean a couple hundred years is still like 5 generations living through it.

I think its fair to correct people on it, knowing what feudalism is and how it failed and was supplanted by parliamentary and absolutist monarchies basically answers the question "why does Europe still have kings?" by itself at the very least.

Additionally, former serfs' newfound tenant-right of their land as the proper age of feudalism ended was undermined to the point of superficiality in all directions; the oppression of the third estate still existed in near-equal measure, the only material change for most of them was the mode of that oppression and, for some, who their primary oppressor became.

Simply put, I think you're giving his position way too much credit, especially considering the tone employed.

I think the point is that feudalism really didn't have this clear end point where absolute monarchies and mercantilism completely supplanted it, first of all; they ran in parallel to each other for a great number of decades and lasted in France specifically via the Ancien Régime right up until the Revolution, so the implication that serfdom was somehow non-existent in the world leading up to the liberal revolutions is very much not a position supported by historic record. Judging and laughing at posters for their suggested lack of knowledge of history seems pretty misguided when considering the omissions of history one has to engage in to believe such a take is historically inaccurate.

Additionally, former serfs' newfound tenant-right of their land as the proper age of feudalism ended was undermined to the point of superficiality in all directions; the oppression of the third estate still existed in near-equal measure, the only material change for most of them was the mode of that oppression and, for some, who their primary oppressor became.

Simply put, I think you're giving his position way too much credit, especially considering the tone employed.

Im not here to defend someones else point but i think you are reading to much into this, my initial read of what the original poster said was simply an (agressive) reaction to the common idea that many people have that European civilization went simply from Feudalism to liberalism or that feudalism=middle ages, etc. Like i agree with what you are saying and it applies to most things in history (can we trully say absolutism has ended if we still have absolute monarchies in the world?) The minutia of when or how it happened seems irrelevant to that point and truly i only responded to Samoyed because he literally asked for feedback if he made some mistake, im not that concerned with the original poster.

Decided to look up feudalism vs absolute monarchy. Do I have it right that the primary difference is:The minutia of when or how it happened seems irrelevant to that point and truly i only responded to Samoyed because he literally asked for feedback if he made some mistake, im not that concerned with the original poster.

Feudalism: Monarch's power derived from consent of feudal aristocrats

Absolute Monarchy: Aristos' power derived from consent of the monarch

Great thread. Most of this is a bit over my head, but seems so interesting. Clearly most of you must be sociology students, lol.

My simplistic layman understanding is that in any form of industry or governance, certain people rise to power. Perhaps through ambition, effort, talent, knowledge, nepotism or just luck. But then they inevitably end up using that control for their own benefit and fucking everyone else. This is Marxist thinking I suppose? After reading through this thread I'm curious as to how accurate this assessment is.

Is there an example of an ideal society that rewards the people who work hard to drive civilization from a managerial or innovation standpoint, but still rewards the working class? And what about the *eat/fuck/smoke/shitpost/repeat* majority that do neither, even with ample opportunity? What do they equitably deserve?

Thanks agian for sharing your thoughts, folks.

My simplistic layman understanding is that in any form of industry or governance, certain people rise to power. Perhaps through ambition, effort, talent, knowledge, nepotism or just luck. But then they inevitably end up using that control for their own benefit and fucking everyone else. This is Marxist thinking I suppose? After reading through this thread I'm curious as to how accurate this assessment is.

Is there an example of an ideal society that rewards the people who work hard to drive civilization from a managerial or innovation standpoint, but still rewards the working class? And what about the *eat/fuck/smoke/shitpost/repeat* majority that do neither, even with ample opportunity? What do they equitably deserve?

Thanks agian for sharing your thoughts, folks.

Decided to look up feudalism vs absolute monarchy. Do I have it right that the primary difference is:

Feudalism: Monarch's power derived from consent of feudal aristocrats

Absolute Monarchy: Aristos' power derived from consent of the monarch

Not quite, in absolute monarchies i believe the nobility normally has lost most if not all of its power(well ideally in the political though of it i guess, not quite sure if in reality), theres no longer a suposed need for the monarch to have vassals to control his land and the nobles always derive their power from their Monarch regardless of that, the change they have is more to do with how much influence they have in each type of arrangement (in the latter they exist cause they have been there for a while basically, sort of how Monarchies do now!). Adding to that i believe theres different types of Absolute monarchies like the Prussian one if i recall correctly